Associate Professor of Environmental Studies Tsegaye Nega and his company, Anega Energy Manufacturing (AEM), were recently featured by the United Nations (UN) as one of six PeoplePowered Energy Solutions around the world.

The UN describes PeoplePowered Energy Solutions as a celebration of “[e]arly-stage solutions by grassroots innovators [that] bring sustainable energy to remote and vulnerable populations.” AEM is a company that builds sustainable cookstoves that are efficient and healthier for both the people who use them and the environment.

Professors Nega and Charles “Jim” and Marjorie Kade Professor of the Sciences in Chemistry Deborah Gross collaborated on an Off-Campus Studies (OCS) program to Ethiopia that has become integral to the project’s success. They shared the story of the work, their collaboration and the inspiration behind it all, which began in 2015.

“I am originally from Ethiopia,” said Professor Nega, “So I kind of know the problems there. When I got an opportunity to travel there again after I started working here, I saw the problem.”

“A lot of people suffer, especially the women and children… Around 60,000 women and children die every year because of indoor pollution due to wood and charcoal use. Another five million people suffer respiratory diseases. Similarly, the environment is impacted by deforestation [due to charcoal manufacturing],” he explained.

Professor Nega’s idea first began when “the first time I went to Ethiopia in a long, long time was for the Off-Campus program to understand conservation issues there. I was very much interested in sustainability — land use and coverage — to develop urban planning.”

He said that the government of Ethiopia was not interested in hearing his ideas, so “I asked myself, ‘How can I contribute?’ That’s when it dawned on me that the one concrete thing I can do without the government is working on household energy problems…We could do something about it.” As Nega is not an engineer, he wrote letters to private companies that “claimed to design cookstoves for poor people in developing countries,” but got no responses.

“These are like my brothers and sisters… I grew up there, so I said I need to do something about this… So I started building cookstoves here,” he said. Then collaboration on the project began when Randy Hoffner from ITS helped Nega build “rocket stoves using buckets… I wanted more sophistication, so we built […] a rocket mass heater.”

At this point, Gross became involved too. “Two things are important: one, I’ve been studying air pollution [and] particulate matter for many years before I came to Carleton — not specifically looking at the context of household cooking in Ethiopia, but on a mass level, like, for instance, McDonald’s; second: I knew Tsegaye and that he was doing interesting things,” she said. “There was a day that Randy was in my research lab because I had a hard drive that crashed. He said, ‘Oh, I have to go, I’m supposed to help Tsegaye with rocket stoves.’ So I said, ‘Tell me more.’ Then he told me a little bit and I said, ‘That sounds really cool, can I come too?’”

Professor Gross was also interested because they were working on clean burning, something Gross had been studying for years. “I sort of invited myself to the party,” she said. “Since then, we have found lots of ways to collaborate with classes.”

That fall, she taught a climate science course that studied the literature on cookstoves which was useful for Nega’s Winter 2016 OCS program. “That was really the beginning of the project… the classes have been collaborating ever since.”

“We didn’t have any designs [for the cookstoves], then we found an Italian blueprint that could work, but we needed someone to build that,” said Nega. He came into contact with the owner of a steel factory in Iowa who offered to build as many as he needed, donating “$25,000 worth of steel” which Carleton helped ship to Ethiopia for the program. The students collected and analyzed data from households who were given stoves about what they liked and what they didn’t, establishing the next steps.

Throughout the years, various people — such as professors from the physics department and a graduate student whose dissertation was on cookstove designs — have come together on Professor Nega’s project as new issues have arisen. Many versions of the cookstoves were designed, built and tested both at Carleton and in Ethiopia. The next students went to Ethiopia in 2018 on a grant from the US Embassy to distribute stoves to local households. “All ten of those people we gave stoves to in 2018 still have and use them,” said Gross.

Using the feedback from those people, Nega designed his own version of the stove to meet their specific needs. Professor Gross said, “Then because […] nobody stepped up to say ‘Oh, I’ll manufacture these,’ he did it himself.”

Happy with the new designs, they found the issue interesting for many reasons. “It is interesting both in terms of its intellectual and climate aspect — for [her] as a chemist and [me] as a conservation biologist,” Nega said. “It is also a very interesting question in the sense

that we could involve the students in this issue. Finally, it is also a practical thing, […] you could actually see the impact of what you do in people’s daily lives.”

The OCS program had originally been term-long, but became a winter break trip instead because students would learn and conduct research over a shorter, more concentrated period of time. The first trip was meant to take place in 2020, but the COVID pandemic began. So, the students, unable to travel, studied over Zoom, which was “not perfect,” as Gross said. “But Tsegaye went to Ethiopia and coordinated a whole team of students from Addis Ababa University who conducted research projects that Carleton students designed.”

Some research projects were about air quality within individual homes; some were about the social aspects of Ethiopian homes, in which women do the bulk of cooking; and others looked at charcoal importation into Addis Ababa and what the impact of the pellet stoves on deforestation might be.

Nega has incorporated those research results into current designs for the stoves. However, Professor Gross says that “separate from [the research], there’s the question about these great stoves: ‘How do you build it?’ ‘How do you market it?’ ‘How do you get it into people’s hands?’ ‘How do you make it affordable if you can?’”

“To do that, [Nega] founded a factory [AEM] that exists in Addis Ababa where stoves can be manufactured and sold… If you do the research and it’s a great thing, you think ‘This could matter.’ That’s all well and good, but if it doesn’t exist, there’s not much you can do,” she said. “So, on nights and weekends, he made it exist.”

“Bringing it to the manufacturing level is a totally different thing,” Nega said. “That takes a lot of money. We wrote a lot of grants.” Due to an internal issue with one of the grants, progress on wide-scale distribution of the pellet stove has been halted. Some of the electrical parts for the pellet stove model can only be imported into Ethiopia, which is expensive. As a result, Nega had to design a more efficient version of the charcoal stove.

“The idea was, let’s improve something else […] that will be a step towards keeping the factory going, but also improving the opportunities for cooking: making things more efficient, using less charcoal [and] producing less smoke,” said Professor Gross.

“There’s no silver-bullet solution for this. We need to be able to be sensitive to the local needs,” Professor Nega said. While the production of pellet stoves is stalled, they now manufacture more sustainable stoves of all kinds: wood, charcoal and industrial stoves for hospitals and schools. “The problem is that this requires an enormous amount of resources. We both work in our free time, so it takes much longer than for another group of people. We just have to follow the academic cycle and get students interested, work with them, go, come back… so it takes a long time.”

“That’s sort of how this project keeps going is by these great infusions of student interest and research that feeds back into our knowledge about what works and doesn’t, so that we can understand what people need. That’s the difference between a standard chemistry experiment [and this],” said Professor Gross.

Not only do they have to have the answer to a particular question, but they also need to know what works for the people involved and what matters to them too. “We could come up with something great in the lab, but it might not cook dinner,” she said. The students’ research, she said, has been really useful for that.

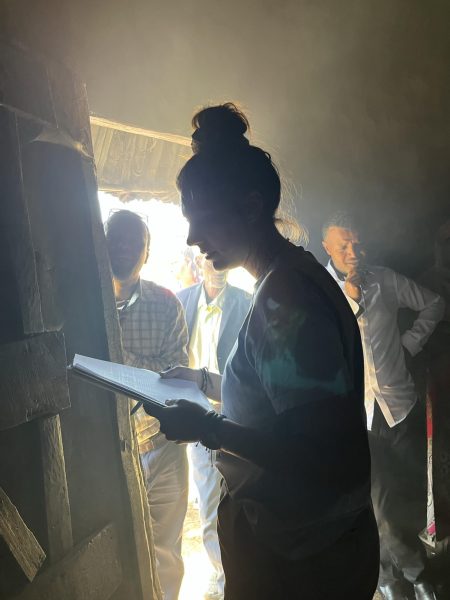

Gross said, “[The students on the OCS trip during Winter Break 2022] were able to now say things like ‘Cooks have been using the stoves for a while: Are they using them right? Are they using them well?’ […] ‘How are kids in school in Addis Ababa educated on climate change?’”

“When you bring students, you need to explain why you’re doing something, and that keeps you on your right agenda,” Nega said. “Of course the commercial aspect is important, but […] the best strategy is to engage the students [to keep the project together].”

Nega said of the UN’s interest in their work: “We were surprised, because unlike other companies, we’re not full time. It’s a great acknowledgement.” They were also selected over the summer as the most impactful company in Ethiopia.

However, for both Nega and Gross, the true acknowledgement comes from the people. “We just want the work done,” he said. “It makes you much happier to see a person who was suffering […] say ‘thank you.’ That’s the most important recognition, from the people we wanted to provide assistance for. That means that we’re accountable to them.”

“I totally agree, when someone says ‘My kid isn’t coughing as much because it’s not as smoky in the house,’ and things like that,” said Gross. “There’s so much talk globally about the UN sustainable development goals and all sorts of things that are really important that we all learn from and pay attention to. I think it is nice that those are being brought down to ground level and that they’re figuring out ways to identify and celebrate people who are working towards those goals. But celebrating doesn’t get anything done.”

She continued, “It’s a good start, but it’s not the be-all-and-end-all. We don’t do it for that.” So, while the UN’s acknowledgement is appreciated, the true satisfaction lies in the people Nega started this for.