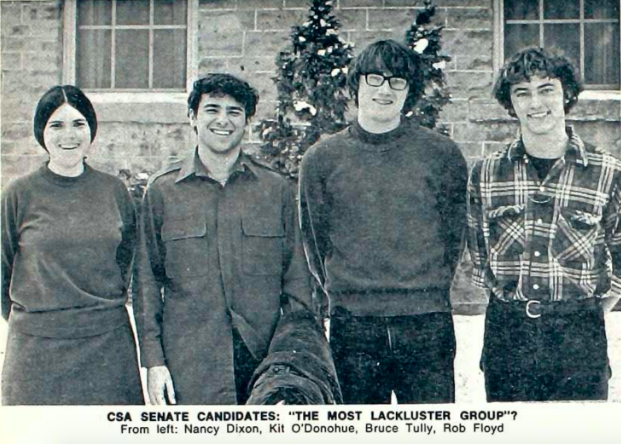

This year’s CSA elections revealed a decline in student involvement. According to the 2020 CSA Executive Report, voter turnout has been steadily decreasing since 2017, from 67% then to only 49% of students participating in the winter 2020 elections. During this spring’s CSA Senate elections, nine of twelve positions went uncontested, and the vote drew a mere 21% of Carleton voters.

To mark the 100th anniversary of student representation at Carleton, we looked deep into the Carletonian archives and found that representatives have long been frustrated with student apathy. The “major difficulty in establishing a meaningful student government,” wrote CSA presidential candidate Mick Parrott ’62, “is the lack of an interested and informed student body.” Since 1920, Carleton students have been complaining about their government system and working to perfect it—or, at least, writing scathing Carletonian op-eds about it.

Students created the Alma Mater Association (AMA) in 1920 to foster a “proper predominating college spirit,” according to the Carletonian, and to unite Carleton students into a single organized voice that could have authority over social events and other matters they considered outside of administrative purview.

Elected members of the original AMA included a President, one male and one female Vice President, and two cheerleaders—usually men, in charge of invigorating crowds at sporting events and pep rallies. Their responsibilities were primarily social, including the “promotion of sportsmanship at college games, prevention of indiscriminate hazing of freshmen, definition of proper college spirit at college parties, and entertainment of visitors at all college entertainments,” founding member John Wingate ’21 stated at the meeting that launched AMA.

Within a decade, students, complaining of the AMA’s failure “to arouse the interest of the students” and to “bring forth a representative expression of the student body,” abolished the association in favor of an organization with stronger executive power and a greater focus on discussing and resolving the issues that mattered most to students. In the fall of 1931, the first Carleton Student Association (CSA) convened, whose basic constitution and representative format we follow today. Broadly, CSA refers to the collective student body; CSA Senate members are its elected representatives. As describe on the current CSA website: “As an enrolled Carleton student, you are automatically a member of CSA.”

The original CSA constitution stated that its purpose was “to provide means for student discussion of any subject which pertains to student life at Carleton, and to provide the machinery to carry on the necessary activities of the student body.” Amendments had to be introduced at a “regular meeting of the association” and published in two issues of the Carletonian before they were voted upon.

Today, the CSA Senate has 25 positions, including office liaisons and class representatives—but at its founding, students could only run for President, Vice President, and Treasurer. Typically, at least two students ran for CSA President, but those aiming for Treasurer or Vice President often ran unopposed.

Kirbyjon Caldwell ’75, candidate for CSA Vice President, kept his Carletonian platform brief: “Since I am running unopposed for CSA Vice President and there is a slight paper shortage, I see little reason for presenting a platform at this time. Take care of yourselves.”

This pithy column was not the only amusing part of Carleton elections that decade. According to the Carleton website, when all ballots were counted in 1977, Joe Fabeetz—an imaginary candidate—had won the CSA Senate election with 1,012 write-in votes.

In the early years, CSA positions were almost exclusively held by men. The first female president, Corinne Leino ’26, was elected to the AMA in 1925, but only a handful of women followed in her footsteps and pursued positions other than secretary. In 1967, that all changed when the first elections were held for the Dorm Senate, a system of representatives based on residence halls, which at the time were separated by gender. That meant there were designated spots in the Senate for women to speak on behalf of their East-side dorm communities.

Throughout CSA’s early years, its authority was undermined by the Men’s and Women’s Leagues, which held sway over many aspects of social life at Carleton and had a greater presence in students’ daily lives than CSA. In 1941, CSA faced termination when some students felt that their governing system was ineffective in the shadow of the more popular Leagues. Herbert Lefler ’42 attributed CSA’s shortcomings to the “apathy of the student body.” He wrote in his presidential campaign letter that “there are reasons for this apathy and that once the disease is cured, the basic ills of our student government will likewise be cured.”

Students nearly moved to dissolve the organization and rely solely on the Leagues to represent their voices. Instead, CSA was saved when they amended 13 articles of its constitution, which incorporated the Men’s and Women’s League presidents into the Executive Council and redefined the duties of the Vice-President.

After the “student government crisis” of 1941, CSA regained its footing. CSA President William Cheek ’39 introduced a mandatory “chapel meeting,” where students came to hear each candidate’s platform, ensuring that the CSA election was not just a popularity contest. Running was almost a full-time job, that included canvassing, collecting dorm contacts, and hanging posters.

“So you want to know what it’s like to campaign for student body president,” said candidate Ted Bergstrom ’62 to a Carletonian reporter. “Well,” he began, “it’s enjoyable, stimulating and doggone tiring. I’ve given up on sleep and studying almost entirely.”

The times when students seemed to be most dialed into their own government was when it was mired in controversy, as it was through much of the 1970s.

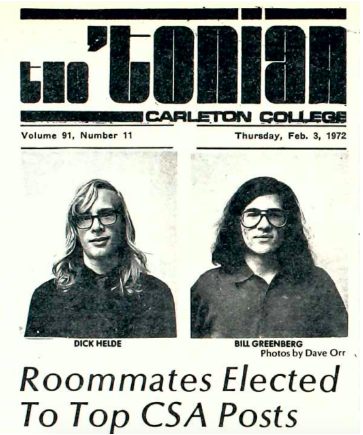

The most notable incident happened in 1972, when the campaign of Dick Helde ’73 was accused of skewing the election in his favor by gaming the preferential voting system, bringing some of the same issues surrounding the rapidly unfolding Watergate scandal to Carleton. Helde’s opponents said that his campaign told voters to cast only one vote for him instead of ranking their choices, which he denied. In the following weeks, there was a re-vote and the runner-up, Robert Strauss ’73, was elected CSA President.

A decade later, a 1989 Carletonian article headlined “CSA Senate ignores student opinion” cited a Senate decision that barely passed (in a 10-8 vote), to allow for a student referendum on the institution of S/Cr/NC. “Clearly the eight senators who voted not to allow a student body referendum were not representing our desire to express our opinion,” Seth Brown ’91 wrote.

The same article criticized the Senate for choosing not to fund the feminist journal Breaking Ground even though “670 signatures supporting the journal were collected in one week.”

The Budget Committee, which guides Senate in allocating CSA funds, became further steeped in controversy when they declined to increase funding for another student organization: the Student Organization for Unity and Liberation (SOUL). Due to a lack of communication between the two groups, SOUL signed a contract to bring a speaker to campus and were not allocated the additional money to cover a rise in speaker price.

Michelle Coffey ’91 and Karen Crawford ’89, executive board members of SOUL, replied with a sharply worded Carletonian article that asked, “will the nature of the CSA’s relationship with its charter organizations be one of mutual cooperation and trust, or one of mutual fear and loathing?”

CSA has had its fair share of struggles with constituent apathy during its 100-year history, as well as periods of high involvement. Today, all CSA platforms and elections are available online, but they remain dependent on a certain level of student engagement. As Alan Hall ’41 wrote in an opinion piece in the May 24, 1940 Carletonian, “there’s something even worse than biting the hand that feeds you; that is paying no attention to a hand which might feed you and then wondering why you starve. The CSA is such a hand.”

Current CSA President Andrew Farias ’21 said that the main thing students need to remember is that “we are all in the Carleton Student Association. Even if it may not seem like it, it’s something that we’re all involved in.” While voter turnout is a valuable gauge of student interest, he noted that filling out a ballot is not the only way to stay engaged.

“Whether it’s sitting on CSA Senate, or attending a meeting, or reading the meeting minutes, or just liking a post on Facebook or Instagram,” Farias said, student involvement is essential to sustaining the presence of CSA in years to come.