In the age of COVID-19, student journalism is adjusting. Across the country, student-run, college newspapers are rushing to go completely online in order to provide information and a sense of community to an outspread network of readers.

Following President Steven Poskanzer’s email on Thursday, March 12, detailing Carleton’s plan to extend spring break and switch to online classes for the first half of spring term, the Carletonian relied heavily on social media outlets to share updates. For example, the publication posted articles and breaking updates on Facebook and created an opt-in online newsletter for all students.

Student newspapers at peer institutions have had similar experiences navigating the shift to the web. On March 18, The Middlebury Campus, Middlebury’s student-run newspaper, hosted a discussion-based webinar titled “College Journalism in the Age of COVID-19.” Seven staff members from the Carletonian attended the webinar, along with 58 student journalists from peer institutions.

Benjy Renton, editor-at-large for The Middlebury Campus, spoke about the experience of organizing and hosting the webinar: “There’s no textbook for coronavirus, there’s no one telling you the thing you should do because no one knows. And there’s no way to know what is right and wrong. I think as people try out new methods and practices, it’s great to share all of that.”

The webinar centered around the task of switching to an online interface. At Bates, the student newspaper has been very active through Instagram. Bates student Vanessa Paolell ’21 expressed excitement at the extent of support from students. “In the last week and a half, our followers have increased by more than 100,” she said.

What are the next steps for student newspapers like the Carletonian, The Middlebury Campus, and The Bates Student? “I think we should see student journalism as a way to get accurate information and get updated information about what the college is doing to deal with this on multiple fronts.” said Renton. “I encourage people to keep thinking out of the box, whether it’s hosting more community forums or events or webinars.”

Renton explained an initiative that The Middlebury Campus is taking: “One thing that we did last week was our top editors put a link out to a form so that people could send in stories about their experience. We’re trying to set up a kind of quarantine diaries. We’re trying to get a small group of maybe 6 people to write about their experiences wherever they are.”

Innovation through technology has been the cornerstone of student journalism over the past few weeks. Paolella, speaking on The Bates Student, said “Even if we can’t be at Bates right now, we can still be together in so many other ways and we’ve had a fantastic time so far trying to put together our first digital issue.”

This in itself—the relative ease of switching from print to online—speaks to the many ways that campus journalism has changed over the years.

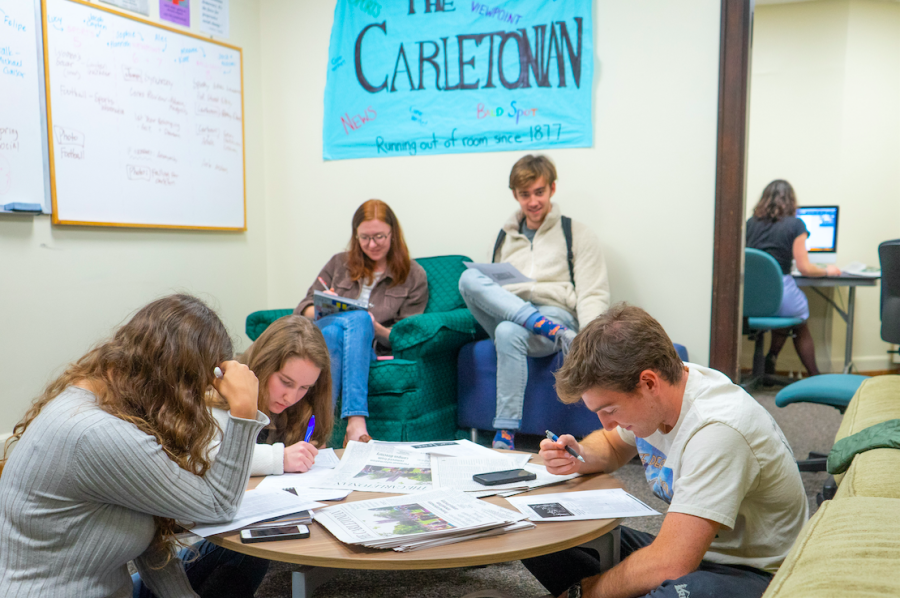

“Journalism itself reflects the culture by evolving in its use of authority, informal language, images, data, and technology” said Carleton English Professor Susan McKinstry. “I think over time the Carletonian functions as a remarkable window into each era, into what was happening, what mattered, how people spoke to and about one another.”

This observation prompts self-reflection for writers and readers alike: what window does the Carletonian (and weekly newspapers at peer institutions) offer right now?

Former Editor-in-Chief of the Carletonian Bruce Lenthall ’90 provided some insight into his experience of the publishing process, including the late-night Thursday printing and early Friday morning ritual of stuffing every student mailbox with a copy.

“All the editors would come exhausted and bleary-eyed and stuff mailboxes,” said Lenthall. “That was a lovely moment because it didn’t require any thought and you were seeing the fruits of your labor. But from the standpoint of students, this meant that every student on campus was getting a paper that day, and every student was looking at the stories in the same kind of way.”

“I think it was a nice moment in which the college was able to talk to itself,” he concluded.

Over the years, as the Carletonian became accessible online, the mailbox tradition lost momentum. Today, not every student receives a personal copy of the Carletonian, but has the option of reading online or picking up a newsstand copy. Gauging readership is difficult as students have almost unlimited access to national and local news sources via the internet.

However, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, student newspapers have demonstrated a continued and evolving commitment to local information access.

Lenthall added some insight into the role of student journalism in the media storm that is covering the coronavirus pandemic, asking “Where does news get made?”

News related to how the college will serve its students is, for the most part, disseminated by the administration. However, Lenthall continued, “That’s not the only place that news gets made. News gets made with the faculty, news gets made with the students. And those voices don’t have the same kind of megaphone to reach the whole of the college. And those voices can circulate in Facebook groups and Twitter feeds and small circles. But not necessarily to everyone.”

Another resounding theme amongst college newspapers is the hope to foster community in “this strange place that we find ourselves,” as McKinstry puts it. “For all of us, wherever we are, the Carletonian can tell the stories we want to hear about the people, the College, the community now.”

“This strange place” is spread out across the globe, students connecting through virtual classrooms and social media. “We’re not all in the same place, eating in the dining halls, going to class together, living together” said Renton. “I think student journalism is a way to bring the community together.”

Expanding on the theme of community, Lenthall added: “What’s most at risk is your sense of connection to this educational project.”