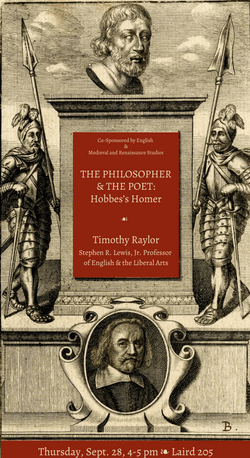

On Sep. 28, Professor Timothy Raylor, Stephen R. Lewis, Jr. Professor of English and the Liberal Arts, hosted a lecture that intertwined the names of Ancient Greek poet Homer and English philosopher Thomas Hobbes and refuted common misconceptions of Hobbes’s beliefs.

The lecture detailed Hobbes’s life and his translation of 48 books of Homer. Raylor started the lecture with a debunking of a popular misconception of Hobbes’ intellectual history: that he started out as a humanist, then, later in life, rejected humanism in favor of a cold, mathematical view of the world. Hobbes was never much of an optimistic Renaissance humanist in the first place, but he didn’t completely reject the humanities either. Throughout his life, he wrote Latin poems and, in his seventies, began working on translating the adventures of Odysseus (Books 9-12). By 1676 — at 88 — he had translated all of Homer’s 48 books.

As Raylor highlighted, Hobbes’s translations weren’t very poetic, and the philosopher added details that weren’t originally mentioned in the original stories. For example, the original Odyssey neglected to mention Elpenor climbing up a ladder before falling off of Circe’s roof. The Hobbes translation described Elpenor’s journey up the ladder onto the roof prior to his deathly fall. The addition was an intentional choice on Hobbes’s part due to his views on poetry. Raylor stated that Hobbes had three main contentions with epic poetry: literary devices that confused and misled readers, frequent bad translations and the field’s reliance on tropes and trends. Raylor explained that to circumvent these problems, Hobbes took on the Herculean task of translating Homer’s work himself. His translations eschewed the grandiosity of previous translations and made Homer readable to women and children, in contrast to the prevailing attitude at the time, which was to make the classics exclusive to men educated in Greek and Latin.

Hobbes is better known for his political philosophy and his harsh view on the natural state of humanity than his work as a translator, so Raylor’s lecture revealed a different side to Hobbes than most people are accustomed to. Hobbes was someone who “had this great zest for life, and this came through in his writing,” as Raylor explained. He said that on a more general level, Hobbes’s translations of Homer show that both the humanities and the sciences have their place in the world. The fact that Hobbes — a person who was thought to have utterly spurned the humanities in favor of modern political philosophy — translated both the Odyssey and the Iliad and made Homer more accessible to women and children, repudiates the notion of the need to reject the humanities in favor of the sciences. In the words of Professor Raylor as he concluded his lecture, “If Hobbes didn’t reject the humanities, neither should you.”