The absence of sports has been noticeable at Carleton this fall. As midterms slowly approach, students, parents and alumni are realizing the times they took for granted when they could pack into West Gym, lay out in the sun for an afternoon at Bell Field, or watch a football game at Laird Stadium.

Unfortunately, no one can confidently predict when athletic competition will formally return to campus. An abbreviated spring season sounds promising, but not if a second wave of the coronavirus strikes this fall or winter. For those in desperate need of Carleton sports-related entertainment, The Carletonian ventured into the archives for something to satiate the sports-hungry.

Carleton athletics hardly ever grasp the national spotlight, but surprisingly enough, a football matchup with crosstown rival St. Olaf garnered national headlines on an autumn afternoon in September, 1977. Along with coverage from thousands of obscure gazettes across the nation, Sports Illustrated, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and The Chicago Tribune anticipated a watershed moment in sports: the first-ever metric football game.

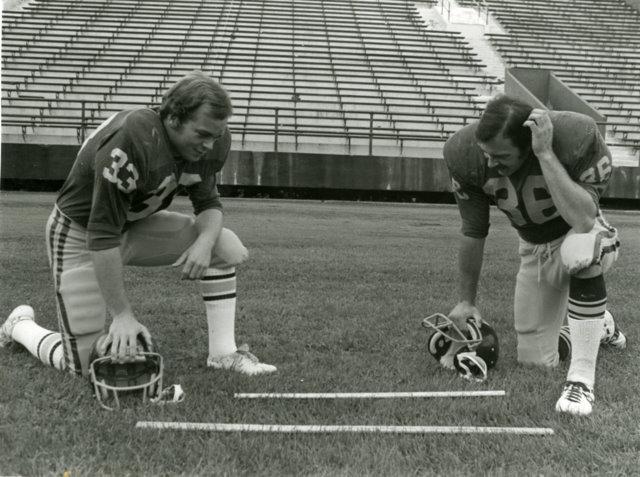

Yes, the concept is quite literally what it sounds like. In place of a traditional gridiron 100 yards in length and 53 ⅓ yards in width, the field at Laird Stadium was extended to measure 100 meters (109.36 yards) by 50 meters (54.68 yards). Yard lines were replaced with meter lines and the first down markers were stretched to 10 meters long. In the media booth, announcers stumbled over their play-by commentary and the official program listed the players’ heights and weights in centimeters and kilograms, respectively. Caught off guard by an undeniably quirky proposal, the NCAA reluctantly endorsed the game, under the condition that official stats were converted into yards before being submitted to the Association’s bureau of statistics.

Such a spectacle was the brainchild of chemistry professor Jerry Mohrig, who along with Dr. Andrew Hulsebosch of the Eastern Analysis Institute, was puzzled with why football, a game so intrinsically integrated with measurement, refused to adopt the globally accepted metric system over the outdated British imperial system. After all, if track and swimming could adopt the metric system, why couldn’t football? The goal, perhaps, was to challenge the notion of American exceptionalism as it related to a game almost exclusively unique to Americans at the time.

The stage was set for the “Liter Bowl,” and for the first time since a campaign speech given by President Eisenhower in 1952, Laird Stadium’s bleachers were full. A crowd of more than 10,000 people clamored about, curious to discover what would happen when a game of inches suddenly became a game of centimeters.

Unfortunately, the ‘Carls,’ as they were referred to then, didn’t quite measure up, and failed to shine in the national spotlight. “All the preparations had been made. All were ready: the fans, the press, and the nation—all but the Carleton team,” read The Carletonian.

Bloopers began before kickoff when a Carleton player dropped a ceremonial first pass from Dr. Ernest Ambler, Director of the U.S Bureau of Standards, who was invited to serve as ‘grand marshall’ for the Liter Bowl. From the get-go, the Carls quickly fell behind the Oles and never managed to catch up. Buoyed by 508 meters of total offense, the Oles trounced the Carls, who mustered a mere 220 meters, and who according to The Carletonian, “did not gain even a centimeter on the ground.” At the sound of the final whistle, the scoreboard read 43-0 in favor of St. Olaf.

Anticipating the buzz generated by the world’s first metric football game, ABC television sent a camera crew to Laird Stadium with the objective of showcasing highlights from the action during Notre Dame vs. Mississippi’s halftime show. Ultimately, the idea was scrapped due to the affair’s one-sided nature and an overall lack of quality football between either team. Thankfully for the Carls, their thrashing at the hands of the Oles was not displayed to the masses on national television.

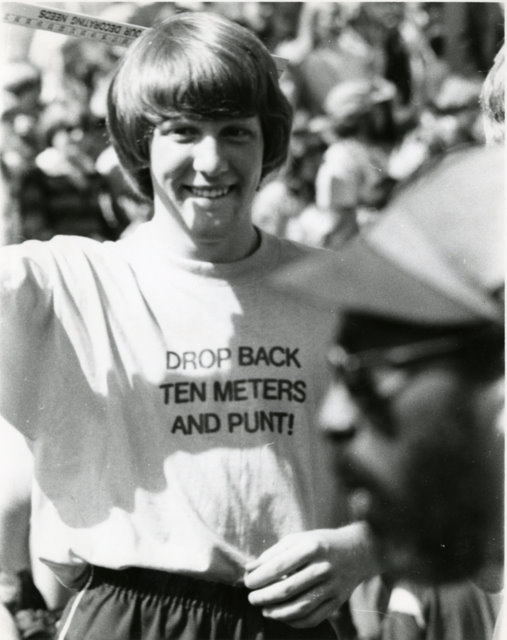

While the football team struggled to contain a strong Ole rushing attack, Carleton students reveled in their own ingenuity. “Cheer liters” stood on the sidelines and “meter maids” ran the aisles to help fans understand the new field dimensions. A bedsheet hoisted by students read “Hey Big Ten! Follow the Liter!” and at halftime, special guests Ulysses S. Gram, Harmon Kilogram and Jean Claude Kilo were introduced to the crowd, all of whom were proclaimed as figures to be reckoned with, “by any standard of measurement.”

For about a week following the game, Carleton maintained a presence in the national news; follow-up articles were written, and the story made an appearance on CBS. That being said, not everyone was thrilled with the college’s publicity stunt. The following Friday, an anonymous editorial in The Carletonian read:

“Before we pat ourselves on the back too much… we should realize that events such as metric football are novelties. Unfortunately, metric football and Carleton College will be forgotten by the American public just as quickly as they gained ‘recognition’ through what is known as media hype. Let’s hope that next time, Carleton football makes big news because it wins.”

Nevertheless, Carleton seized an opportunity to display its creative levity for the world to see. Reporting on the game, The Carletonian’s news section featured an interview with George Dehne, who at the time served as the college’s director of public relations. “The most important benefit of publicity,” Dehne considered, was “the increased pride that the entire student body feels in having enough ingenuity to attract national attention.”

The event symbolized the playful nature of Carleton students and professors, who despite their academic accolades, refuse to ever take themselves too seriously. Additionally, Carleton’s cooperation with St. Olaf in hosting the event represented a strong partnership between two innovative schools who were (and are) always pushing the boundaries of conventional wisdom. Unfortunately, metric football came and went, but its memory lives on.