Carleton seems to be on track to adopt one of the most aggressive carbon neutrality programs of any liberal arts college. The Board of Trustees appears likely to formally approve a proposal for Carleton to be carbon-neutral by 2025 in a vote this weekend. The proposal was part of a strategic plan college president Alison Byerly sent to the Carleton community this past August for feedback.

“I don’t want to speak for the Board, but they have been very supportive in conversations thus far,” President Byerly said in an interview last week.

The proposal, introduced in the Carleton 2033 Strategic Direction draft plan, was crafted by the college’s Environmental Advisory Committee, which advises the college’s Vice President and Treasurer on environmental issues. It lacks details that would appear in a comprehensive plan if formally adopted, but its approval would make Carleton carbon-neutral well before its previous goal of 2050, which was set in 2007.

Assuming it will be adopted, as President Byerly made seem likely, a detailed plan will be completed during the 2024 Winter Term, said Dr. Sarah Fortner, director of sustainability and head of the college’s sustainability office. It will be drafted by the sustainability working group, a larger student-led council that establishes climate goals based on comments from the broader community.

A final plan would not significantly affect campus life, as it would primarily involve Carleton aiding other institutions in reducing their emissions rather than immediately cutting emissions on Carleton’s campus, President Byerly and Dr. Fortner said.

The 2025 proposal does not intend for Carleton to become fully green — or to produce no carbon — in the near future. The college will still rely on some fossil fuels to maintain its operations, but will shift towards having a net-zero impact on the environment by making donations towards others’ emissions through a process called offsetting. Gabriel Kaplan ’25, a member of the Sustainability Working Group, described the offsetting process, saying “For those emissions that [Carleton] cannot reduce or [has] not yet reduced, [it] can partner with an outside firm [to] create a reduction elsewhere that would not otherwise have happened.” If Carleton were responsible for emitting 11,141 metric tons of carbon dioxide one year, as it did in the 2022 fiscal year, it could still be considered carbon-neutral if it helped reduce another institution’s emissions by the same amount. This is a critical step in slowing pollution, according to President Byerly, who says that, “as it is for everybody’s climate action plan, the last mile is the work you do to try and compensate for what you haven’t yet reduced.”

According to Kaplan, the college could donate to help another institution build green infrastructure, or it could assist in reducing the amount of carbon emitted in states that have “cap and trade” emission limits. In states like California, companies are allotted a certain number of emission credits, and those who wish to emit more than the limit must buy credits from those who emit less. If Carleton works with a climate organization to buy and “retire” credits, it reduces how many credits can be traded, thus lowering emissions. In any case, however much pollution Carleton’s offsetting has reduced can be considered to cancel out on-campus emissions.

Though there is no detailed plan yet, those driving Carleton’s push for carbon neutrality indicated that prospective partner organizations will also prioritize education as a main goal. “There is a strong desire to work toward a portfolio that is more local or regional,” said Dr. Fortner, “where we can engage students and have greater oversight.” She also anticipates that early stages of the plan will include collaboration with Second Nature, a nonprofit that works with higher education to reduce carbon emissions through both of the aforementioned means. The college’s Center for Community and Civic Engagement has already contacted Second Nature for aid in reducing emissions by diverting local food waste to community food shelves.

Offsetting emissions will cost Carleton “several hundred thousand dollars a year,” President Byerly predicted. “In the short term, there are ways we can cover [offsets] through reserves and funds that are available, but to support them over time would require probably building the endowment.” A later iteration of the draft plan proposed that the college create a “Sustainable Future Fund” open to support from donors. President Byerly assured that students’ families would not feel significant additional financial strain if the plan were enacted, saying it “will be among the many things that your tuition dollars do pay for, but in the context of the college’s overall budget, it would not in and of itself lead to a noticeable tuition increase.”

Though the 2025 neutrality plan would not focus on reducing on-campus pollution, Carleton has still spent much of the last two decades investing in green infrastructure. According to the Carleton Utilities Master Plan website, in the past twenty years, campus infrastructure has changed drastically in a way not seen since the 1900s, significantly reducing Carleton’s electricity usage and fossil fuel dependency. Carleton added two wind turbines to the local electricity grid in 2004 and 2011, which currently produce around 50% of the school’s electricity. The college also installed solar arrays on the roofs of the Cassat and James dorms in 2009, allowing them to become LEED Gold Certified — an independent rating denoting high sustainability in building design. Furthermore, Carleton built a geothermal water heating system below the Bald Spot, Mini Bald Spot and Bell Field between 2017 and 2018, reducing the college’s reliance on natural gas for heating and cooling.

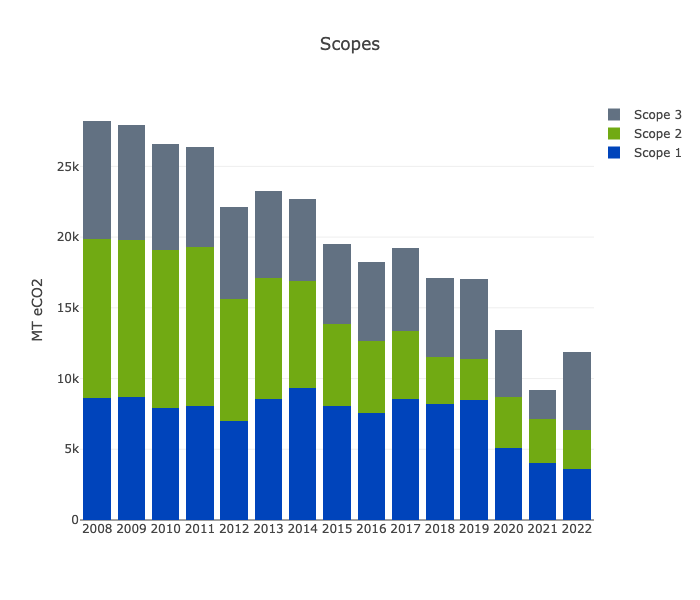

In the construction of Carleton’s newest buildings — most notably, Evelyn M. Anderson Hall, the Weitz Center for Creativity and the new interest house locations currently under construction — energy efficient insulation is central. These projects reduced the college’s net emissions by 58% between 2008 — when it began tracking its carbon footprint — and 2022, dropping from producing more than 27,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide in a year to just over 11,000. Carleton’s 2022 emissions lie 20% below the college’s initial projections for its 2025 emissions.

In early February 2023, amid pressures from the broader Carleton community, the college Board of Trustees voted to divest the college’s endowment from investment in fossil fuels. The Board anticipates the process will be complete by 2030.

This is why the college is now considering pushing up its goal to become carbon-neutral from 2050 to 2025. Said President Byerly, “we’re able to accelerate our goal so substantially [because of] work that has already gone on with the geothermal wells. We’re pretty close to getting there.”

But, even with these changes, Carleton will still need offsets to be carbon-neutral, at least for the foreseeable future. The college’s emissions can be broken up into three categories, or “scopes,” two of which can be lessened with time and investment, but one of which is nearly impossible to lessen.

“Scope I” and “Scope II” emissions are reducible; they account for emissions created and used on-campus or created off-campus and used on-campus, like burning natural gas for heat or using non-green electricity from the public grid. Carleton has reduced these emissions by around 68% over the last 14 years through its infrastructure upgrades, and they went from accounting for 72% of all emissions to just over half. “Scope III” emissions are created and used off campus. Transportation to and from campus makes up the majority of Scope III emissions, and while they fell by 34% between 2008 and 2015, they have plateaued since then. Unless students are able to stop flying and driving to campus, those emissions will only be reduced by transportation itself becoming more green.

The proposal for accelerated carbon neutrality is only the next step in Carleton’s efforts to become more green, and many wish to see the momentum continue. As President Byerly said, “our expectation is that [achieving neutrality] by 2025 would involve a use of offsets that would diminish over time as we continued to increase our energy efficiency.” In the same Carleton 2033 draft plan where 2025 neutrality was proposed, there are proposals to eliminate on-campus natural gas use within 10 years, expand the Environmental Studies department and create a “Center for Sustainability” to coordinate sustainability efforts throughout the college’s curriculum and operations. Enacting these proposals would help reduce on-campus emissions and Carleton’s need to offset other institutions’ emissions to maintain neutrality, and could create opportunities for Carleton to work with the city of Northfield and St. Olaf College to support sustainability in the local community.

If — and seemingly, when — the 2025 carbon neutrality proposal is adopted, Carleton will be one step further towards going green. Looking toward that future, Dr. Fortner said “[i]t’s exciting to think about what is next!”