Tu B’shvat, known colloquially as “the birthday of the trees,” is a Jewish holiday celebrated on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Shvat. In Biblical times, this was the start of the tax season, the day where farmers would pay their tithes in fruit. Today, the observance of Tu B’shvat is not just a celebration of the wealth of fruit-bearing species in nature. It is also celebrated as a call to action for environmentalism, conservation and sustainability in observance of the Jewish commandment to be “shomrei adamah,” or guardians of the earth.

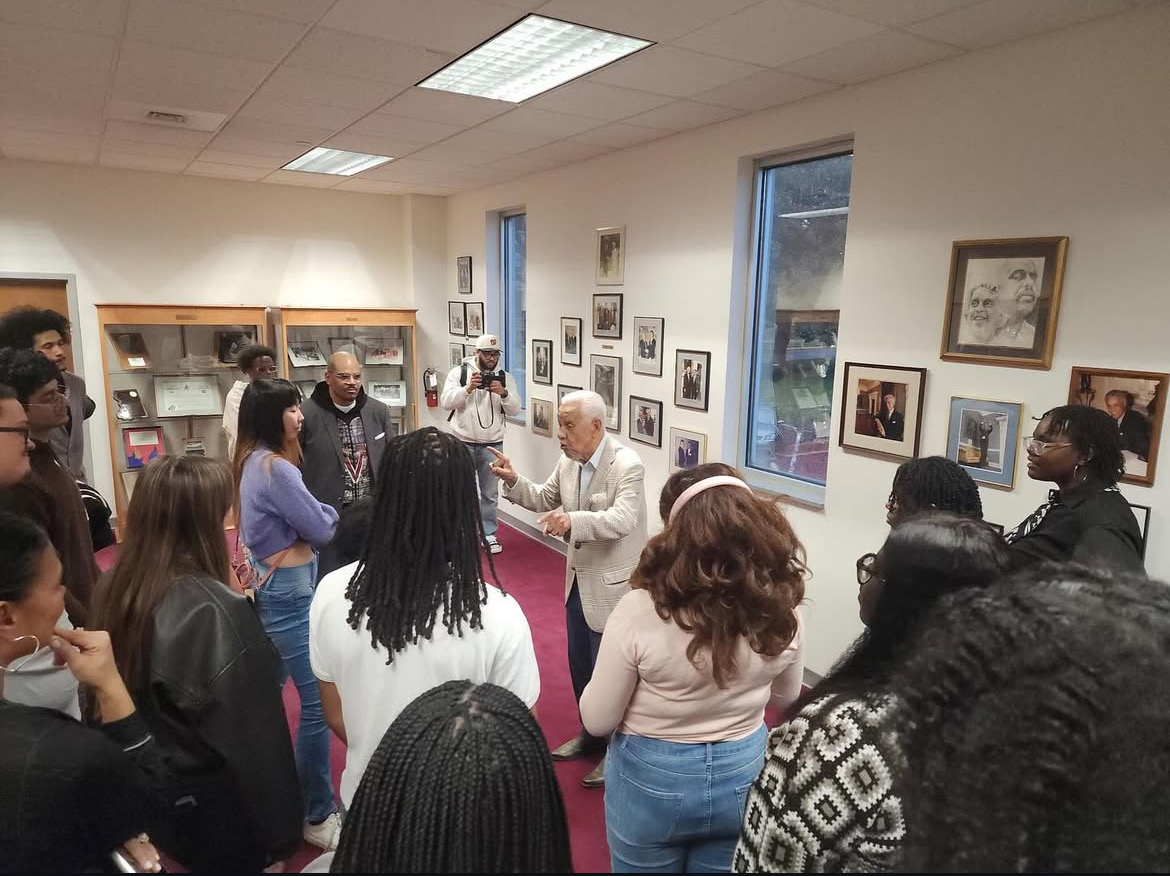

On Friday, Jan. 19, students and staff from Carleton and St. Olaf as well as Northfield community members gathered in the Alumni Guest House for a commemoration of Tu B’shvat with song, reflective reading, a festive meal and a lecture by St. Olaf Assistant Professor of Biology and Environmental Studies Jake Grossman about the inner workings of trees and how they communicate. After a few Shabbat blessings, attendants sat around tables sharing different kinds of fruits and nuts that represent different human temperaments.

First, participants ate pistachios, oranges and pomegranates, whose hard, protective shells, according to Rabbi Shosh Dworsky, represented those who display a tough persona to the world but are emotional and sensitive on the inside. Next, guests ate dates and olives with an edible exterior and a pit in the middle, which according to Dworsky, represent those who appear open to the world but are closed-off on the inside.. Apples, grapes, almonds and raisins, which are entirely edible fruits and nuts, represent the open, reliable, sustainable community that people should strive to achieve. During this ceremony, or seder, participants drank four glasses of wine or juice to represent the four seasons. White grape juice represents the cold, snow-covered, colorless winter, red grape juice represents vibrant and colorful autumn and mixes between the two represent spring and summer.

After a festive meal provided by Bon Appetit, participants settled back into their seats for Grossman’s talk. Grossman currently teaches biology and environmental studies at St. Olaf, but has previously worked in outreach at an arboretum, and currently researches the effects of climate change and biodiversity loss on trees and other terrestrial organisms. He began his speech with an interactive activity to stimulate discussion, saying, “Imagine if you were a tree, what would you tell the other trees around you?” This question yielded a wide variety of answers, ranging from trees telling other trees about incoming threats to sharing resources to telling other trees to leave some room for growth. With these answers, he asked another question: “How do you think trees communicate?”

This question led into the heart of Grossman’s talk. When he was working in an arboretum, he read a book called “The Overstory” by Richard Powers. The heart of this novel is a group of people coming together to save forests from destruction. From this book, he came to learn about a new scientific discovery regarding how trees communicate with each other. The phenomenon of mycorrhizal networks involves fungus, called “mycorrhizae,” living in plant roots and linking them to help trees transfer nutrients to each other. “Western ecologists have mostly focused on competition between organisms,” Grossman said, so this discovery about how trees can work together inspired and uplifted many who read literature about mycorrhizal networks.

But, Grossman’s lecture had a twist. Speaking further about mycorrhizal networks, Grossman said, “It’s a very provocative and newly evolving field of science, but it has little to no basis in fact.” As the audience sighed in disapproval, Grossman admitted that “It’s kind of a big bummer.” However, he explained that mycorrhizal networks are not the only way that trees work (or don’t work) together. “The ways [trees] collaborate are in some ways more exciting than using fungi as their intermediary,” Grossman said, as he explained concepts like clonal networks, natural grafts and volatile organic communication. Trees, while they might not communicate through fungi, can “talk” to each other through chemical signaling and even the interweaving of roots between different species. “The trees are speaking to each other,” Grossman reassured the crowd. And while he acknowledged that evidence of mycorrhizal networks is extremely limited, he said that “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence,” and that while the mechanisms that make these networks possible are very hard to measure, they may very well exist.

After the lecture, Dworsky concluded the celebration with readings and songs about the gift of nature and how Jews are called to protect it. She spoke about the Garden of Eden, where Adam and Eve, the first humans in the Biblical creation story, were presented with a rich garden with many different plants. God told Adam and Eve that they could eat from any tree they would like, except one: the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. But Adam and Eve did eat from that tree, and thus were cast out of the garden forever. Dworsky interpreted this story with an environmentalist perspective, saying that “the first sin of humans was environmental overreach.” Throughout the celebration, Dworsky made sure to acknowledge students, staff and community members who were doing work in environmentalism and sustainability. Of those mentioned, members were present of Divest Carleton, Environmental Carls Organized (ECO), Interfaith Social Action (IFSA), student workers for the Office of Sustainability and St. Olaf’s Biology club.