Although the majority of Carleton’s student body is on campus this fall, academic life remains predominantly online.

Carleton gave faculty members the discretion to choose between four different instructional modes for their Fall Term courses—online, hybrid, mixed mode and face-to-face. Hybrid courses include online instruction alongside mandatory in-person components. In mixed mode courses, some students participate entirely online while others engage in in-person activities. Students who did not return to Northfield this fall are only eligible to enroll in online and mixed mode courses.

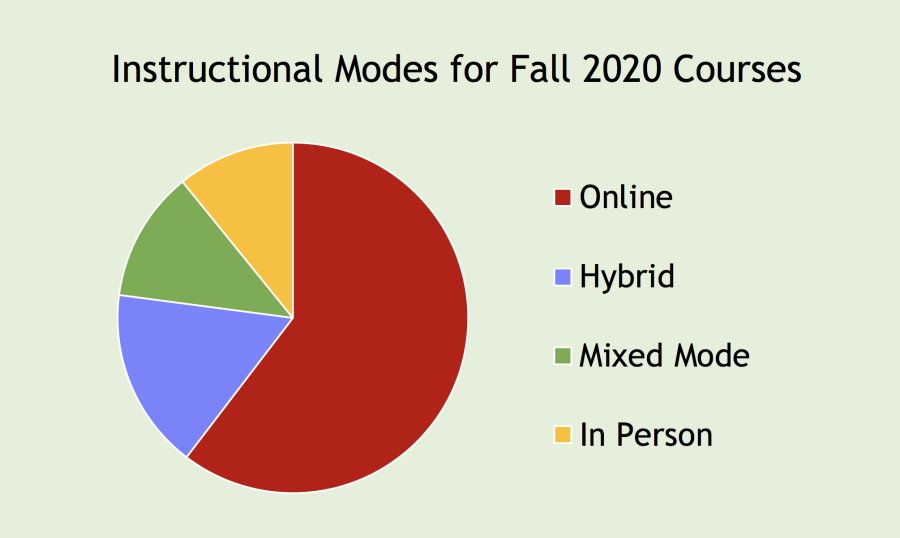

The Carletonian investigated course data on the Hub and found that about 60% of Carleton classes are being taught entirely online this fall. The College originally announced that “about half” of courses would be taught completely online, according to the initial reopening plan email sent by President Steven Poskanzer on July 10.

The hybrid mode was the next most popular option after the online mode, with 17% percent of classes being offered in this format. The mixed mode and face-to-face options each account for just over ten percent of Carleton’s Fall Term offerings.

This means that about 72% of Carleton’s course offerings are available to off-campus students, while 28% are unavailable.

Almost half of the face-to-face offerings are courses with fewer than six credits, such as comps and labs. Across all departments, the Hub lists only 19 six-credit classes taught entirely in-person, out of the over 300 courses offered this fall.

The Carletonian’s data does not include music lessons and physical education classes, but it does include all other listed classes regardless of number of credits.

Departments adopted a wide variety of strategies when making decisions about instructional modes. Most shied away from fully face-to-face courses except in cases where hands-on learning is essential, such as lab classes.

The Economics department is an exception—four out of five sections of its introductory courses are taught face-to-face, along with two upper-level courses.

According to Department Chair Mark Kanazawa, the economics faculty designed a preliminary curriculum over the summer in which most courses would be taught face-to-face.

“We wanted to provide sufficient in-person opportunities to maintain the strengths of a Carleton residential liberal arts experience,” he explained.

When the department made its plan public, however, it received pushback from students. According to Kanazawa, the department received an email signed by 26 of its majors asking that more courses be offered online. Students were particularly concerned about the health risks associated with in-person courses.

“After a follow-up survey of our majors confirmed a widespread desire among students for more online options, we modified our modes of instruction accordingly,” Kanazawa said. The department is now offering a section of microeconomics and five upper-level courses online.

On the other end of the spectrum, the language programs—with the exception of a couple small, mixed mode courses in the Classics department—made a collective decision to offer exclusively online instruction.

This decision hinged on the particular role of speaking and listening in language courses, according to Scott Carpenter, chair of the French and Francophone Studies department.

“When people are learning a foreign language, they need to be able to hear the professor and other students clearly, and seeing the mouth of a speaker helps one both to understand sounds and learn how to reproduce them,” Carpenter said. “Masks and social distancing complicate both of those things.”

Language instruction also depends heavily on small group discussion, Carpenter said, which is easier to implement in Zoom breakout rooms than in a socially distanced classroom setting.

Spanish Department Chair Yansi Pérez echoed this sentiment. “We felt that as difficult and far-from-ideal online instruction is, it was the most logical choice for us,” she said. “We miss our face-to-face interactions with students terribly.”

Other departments attempted to balance health and equity considerations with a particular need for in-person activities. The Art and Art History department elected to offer all of its studio art classes in the hybrid mode. This decision, according to Department Chair Ross Elfine, was based on the “resolutely material and hands-on nature of studio art instruction and learning.”

The Chemistry department took a similar approach, offering any class with an accompanying lab as a hybrid course.

“The overriding principle was to offer an in-person lab experience in courses where working with your hands with the chemicals, glassware, and equipment is an essential part of the learning,” said Department Chair Daniela Kohen.

This, however, could pose difficulties for off-campus students who miss out on sequenced courses. In a small number of cases, exceptions were made for seniors who needed to take a required lab class that is only offered in the fall, Kohen said.

The Physics department was in a similar position—its major requires a Fall Term sophomore course with an equipment-intensive lab. The department opted to split the class into an online theory course and a face-to-face lab, giving students the option to take the theory portion this fall and the lab next fall.

“If students were unable to come back to campus, then they might not be able to major in physics if we structured the class as normal,” explained Department Chair Marty Baylor. “So we restructured the course.”

In many departments, such as Political Science, Dance, and Linguistics, each faculty member simply made an individual choice about how to offer their classes, according to the chairs of these departments. These decisions balanced a wide range of personal and departmental considerations, including health concerns, course enrollment numbers, requests from students and individual teaching style.

The College prioritized allowing first-year students to enroll in at least one course with an in-person component, according to the student COVID-19 FAQ webpage. This included offering Argument and Inquiry (A&I) seminars with an in-person component wherever possible, although 42% of A&I seminars remain fully online.

In the history department, which hosts several A&I seminars and typically sees a large number of first-year students overall, half of this fall’s classes include an in-person component.

“We wanted to give as many first-term students as possible the opportunity to have at least part of a class taught in person, but we also realized that we needed to keep our classes accessible for students who were in other timezones or would end up in quarantine,” said Department Chair Serena Zabin.

Comparing current Hub listings with the provisional course schedule sent out by Registrar Emy Farley in mid-July indicates that many professors changed the intended mode of their courses between July and the beginning of Fall Term. The shift was predominantly towards more online instruction.