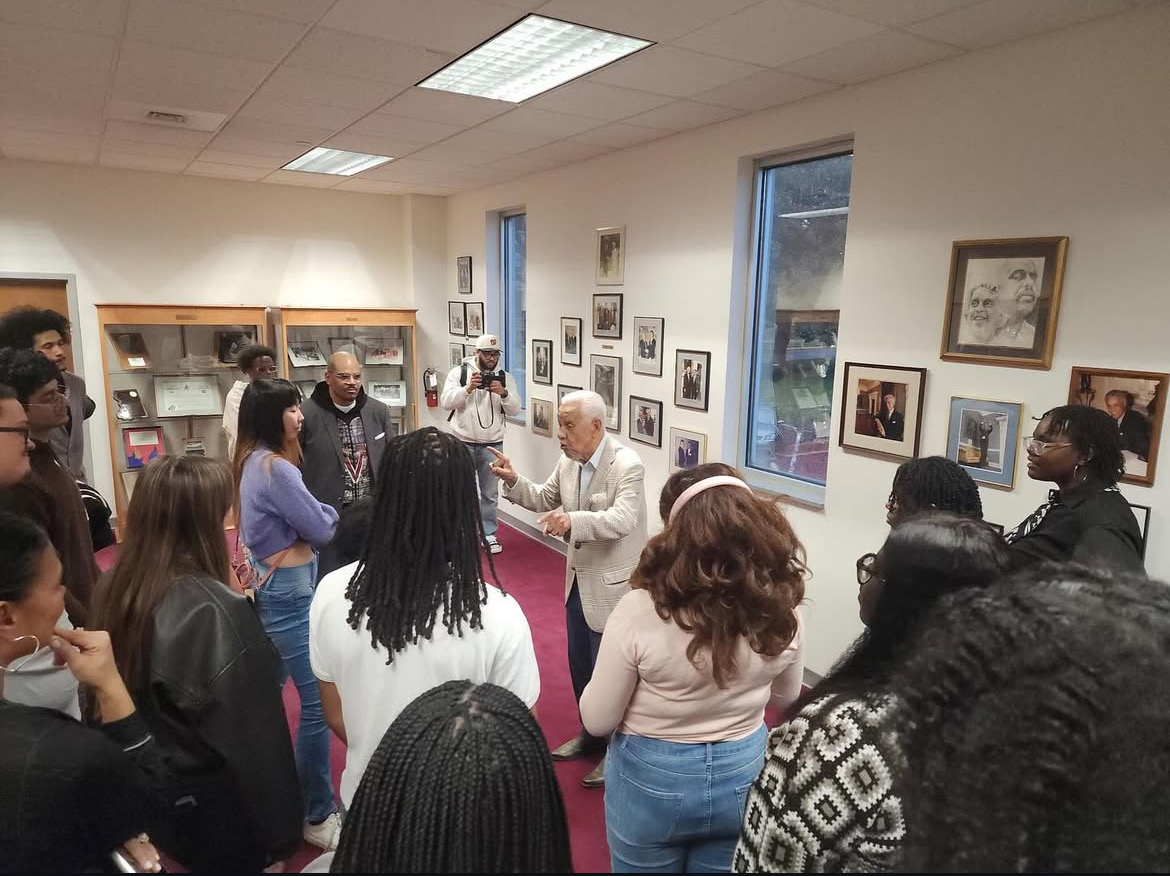

On Oct. 23, the Middle Eastern Languages Department and Arts at Carleton hosted a lecture entitled “Music Making in Palestine During the First Half of the Twentieth Century: Agency and Innovation.” The lecture was attended by students, professors, staff and community members.

This talk was given by Dr. Issa Boulos, known in the music world as a composer, lyricist, oud player and educator. Yaron Klein, Director of Middle East Studies (MEST) and Senior Lecturer in Oud, introduced Boulos, discussing his accomplishments in each of these areas.

Boulos, who grew up in Palestine just before the First Intifada in 1987, has studied both classical Arab and Western musical forms. He is “bi-musical” as Klein put it, and his compositions have been performed by a variety of ensembles, including the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

While visiting Carleton, Boulos visited a number of classes, and hosted an afternoon jam session and evening concert on Oct. 24.

In the introduction to his lecture, Boulos foregrounded the concepts of agency and innovation. Both, he said, are features of the music that came out of Palestine during this time period when ideas like nationalism and identity began to take precedence after the British mandate of Palestine in 1922.

“The whole notion of nationalism as we understand it now wasn’t exactly clear among Palestinians,” said Boulos. But, as his research has found, “Palestinians were at the forefront of navigating all of these different ideological platforms, terrains of thought that entertained ideas about how to come together.”

Boulos said that this was prevalent “particularly at this time of the British mandate, which enabled Palestinians to build institutions, allegedly, to become the basis for building the country.”

While the lasting effects of the mandate have split the area into present-day Israel and the occupied territories of Palestine, Boulos said that “Palestinians, however, benefited a little bit from some of the institutions” that were established, especially with the formation of the Palestinian Broadcasting Station (PBS).

In this presentation, Boulos highlighted the musicians he has found throughout his research, along with sheet music, recordings, and testimonies that reveal the established nature of music recording and producing in Palestine as early as the 1910s. He said that because of the constant displacement faced by Palestinians during the early 20th century, tracking these sources and individuals is extremely difficult.

“Most of the things you are going to hear today are recordings of things that no one has. They are rare recordings,” said Boulos. The documents, recordings and objects like instruments have been compiled by him and a team of volunteer researchers. The process has often involved reaching out based on tips to people in neighboring countries, like Lebanon and Syria. “They would scratch their heads, and come back and say, ‘You know, let me just try and see if I can do anything about it.’ They would come back, two or three years later, after so much nagging.”

These documents have allowed Boulos to learn that one musician who recorded extensively, Ahmad al-Shaikh, was doing so even as early as 1906. Boulos has found up to 55 long playing records that were recorded by al-Shaikh, and based on his recording activity was able to place his time of death around 1914.

He acknowledged, however, that this “Information can change over time, because we are chasing ghosts.”

Other musicians, such as Thurayya Qaddura, were discovered to have moved to other Arab countries like Egypt and Tunisia. Reflecting on this, Boulos said, “This tells you how difficult it is for us Palestinian researchers to track down the journeys of Palestinian singers and musicians.”

“Thurayya Qaddura is a very interesting figure,” said Boulos. He cited a number of reasons, the first being that she is a female singer. “Not all female singers in the 1920s would pick up a poem that is thirty years old, by A’isha Taymur, who was considered then the leading figure of the feminist movement in Egypt,” he said. But Qaddura “picked up this poem and sang it in the music itself. I find that fascinating.”

He added that “It is really really hard, very difficult to find any of the female singers singing anything from female poets.”

The specific song that he mentioned was released in Egypt in 1931, and “of course, there is no mention of her being Palestinian.”

“That’s another set of problems that we face as Palestinian researchers,” he said. Due to “the geopolitical forces that are always present when it comes down to Palestinians articulating their heritage.” He went on to play the recording of the song by Qaddura, highlighting her commanding voice as being very distinctive.

There were similar cases with musicians like Nuh Ibrahim and Nimir Nasir of Yaffa. “Yaffa’s population was around 75,000 people. After 1948, only 3,5000 Palestinians remained,” said Boulos. They had either been killed or fled to neighboring Lebanon, Syria or Jordan as refugees.

Nuh Ibrahim “started putting out some songs on his own… they resonated with how typically folk music works,” said Boulos. He explained that folk music tends to describe day-to-day experiences. “They can be political, they can be social… they can address any subject matter” and is boundaryless in what materials it can cover.

However, at this time, the British began to implement certain censorship around what could be discussed in songs. “You could express your love of the country, how green it is,” he said. But anything that hinted at political dissent or critiques, he explained, was censored. “When the revolution hit in 1936, [Ibrahim] gradually started to conflict… he sang patriotic songs” about the beauty of the country “But he wanted to do something different that he wasn’t allowed to — he was warned, repeatedly. Finally, the British, in February of 1937, issued an arrest warrant and put him in jail for five months.”

Nimir Nasir, a friend and contemporary of Nuh Ibrahim from today’s West Bank, faced a similar fate of censorship and imprisonment for his music. “The whole idea of agency, meaning Palestinians having control over their own expression, was already taking shape,” Boulos said, “But in a very cautious way.”

Similarly, innovation began to take shape in Palestinian music at the time. Radio stations like PBS and Egyptian outlets were the first to be established in the region. He mentioned that these radios were especially prevalent with the Egyptian influence on pronunciation, particularly because of its political influence and because it was home to the radio station before Palestine. Certain musicians, he discussed, resisted conforming entirely, pronouncing certain things such as the letter ‘jiim’ in the Palestinian and Levantine way.

“Once the Palestinian Broadcasting Station was established by the British in 1936… the Palestinians found an opportunity to get something going” and to find a musical niche.

One musician in particular, Yusuf Adwan, explored “that concept of ‘how can we synthesize all of these different types of musics’ — musics — ‘and make them one while keeping the mukhasasiyya, or the flavor of each nation or type of music.” For example, one important aspect of Iraqi music is “Georgina,” a rhythm that sits in 10/8 time. Different aspects such as rhythm or verse styles unique to different types of Arab music were incorporated into songs. Within the vocals themselves, different dialects like the Egyptian one appeared.

“All of these things,” Boulos summarized, “required Palestinians to think differently about how they make music, how they bring all these ingredients together, and how they make them appeal to the region.”

“[Palestinians] started positioning themselves as pioneers in doing so,” he said. Palestinians and Egyptians were at the frontier of music recording, with the best musicians in the region coming to both countries specifically. During this period, anthems became popular, with the current national anthem of Iraq coming out of this innovation.

Throughout this discussion, Boulos played several recordings that he and his fellow researchers found, including a few songs for children, orchestral works and ones about oranges, a fruit Palestine was known for, titled “il-Burtu’an” and “Hilu Ya Burtu’an.” He said that certain phrases sung in these songs are still used in everyday Palestinian speech, and are a result of deliberate efforts to collect and preserve the writings of poets and musicians.

“Of course all this [broadcasting] ended here,” Boulos said, at that moment, pressing play on the last recording for the lecture: “In the files, I found this.” This clip was dated in 1948 and was a recording of gunfire surrounding the Palestinian Broadcasting Station. “They were making their way through the area, and shooting at the Palestinian fighters who were trying to protect what remained of the Arabic section of PBS,” he said. The recording was taken by Rex Keating, the Assistant Director at PBS. In it, he documented approximately five minutes of the fighting. “I got chills,” Boulos said. As the gunfire played, the lecture hall listened in silence.