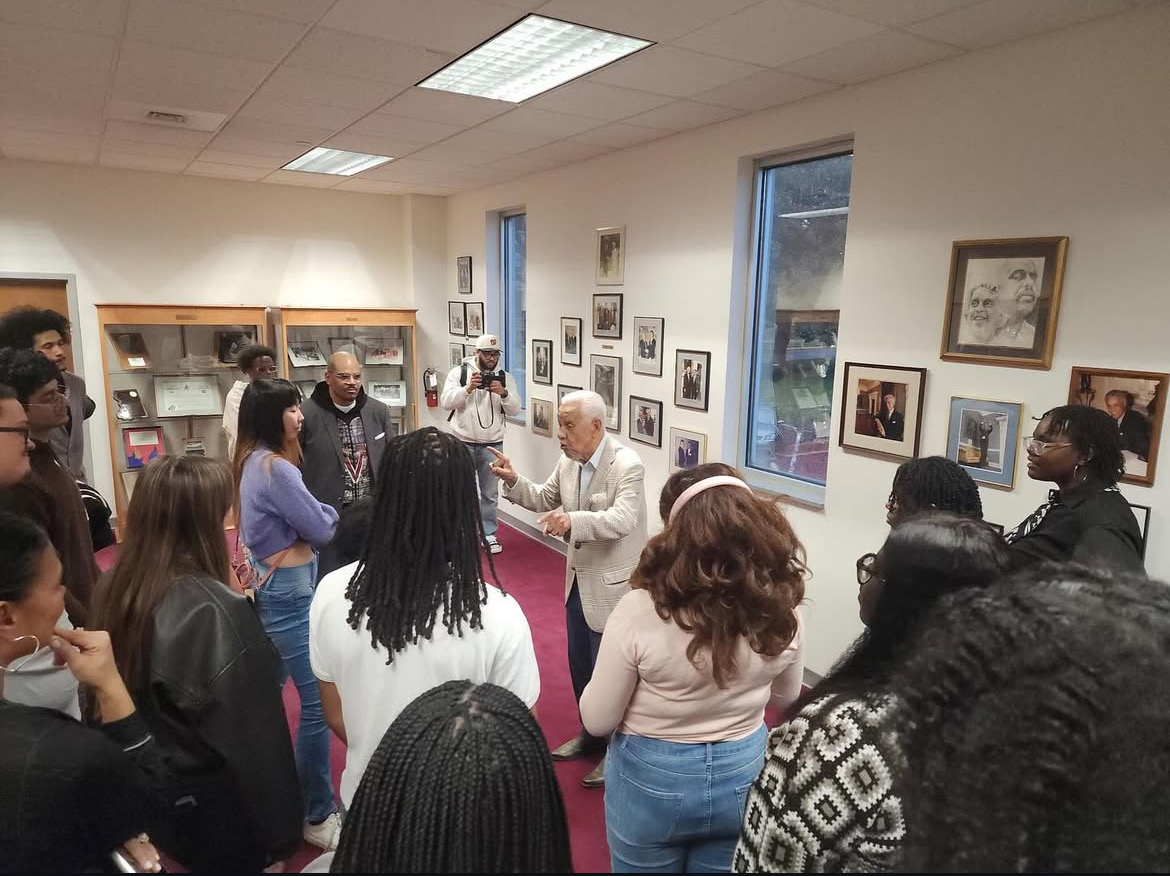

On Wednesday, Oct. 16, students, faculty and staff gathered in Leighton Hall to listen to Dr. Cynthia Chapman deliver a talk about the role of the Bible and religion in the American political landscape.

The event began with Professor of Religion Kambiz GhaneaBassiri introducing the Religion Matters forum. He explained how the forum allows for distinguished scholars in the field of religious studies to “talk about their own work, and show that religion matters by talking about the intersection of religion and public life.”

Ghanea Bassiri proceeded to introduce Chapman and describe her work as a scholar of the Hebrew Bible focused on the topics of gender, social life and warfare in the Bible as well as the role of the Bible in American life.

As Chapman began her talk, she noted that her previous academic experience is quite different from the subject of her lecture, revealing that “[y]ou can tell from my introduction that I am the most comfortable in the Iron Age.”

Chapman, a professor at Oberlin College, began teaching a course about the Bible in American politics in 2016; she has since taught it every other year since to be in step with the election cycle.

“From our nation’s founding, the Bible has always been a part of American politics,” Chapman said. She explained how from the very beginning of American government, presidents have continued to be sworn in on Bibles, signifying its important symbolism.

The majority of Chapman’s talk centered around lawn signs, an avenue through which “the Bible has entered the public domain.” This entrance, she said, was sparked by the Moral Majority led by Jerry Falwell. Lawn signs that bear messages like “Vote the Bible,” “Vote Biblically” and “God and Country” seem to communicate a simple message, but Chapman’s goal was to “give some complexity behind the signs.”

She began by deconstructing the possibilities within the term of “The Bible.” Chapman listed the many different canons of the Christian Bible as well as the Jewish Bible, as well as the variety of translations of each canon. Beyond that, politicians often employ specific verses or sections of the Bible, and each of those sections garner meaning through certain translations.

She led the listeners in an exercise where she displayed two Bible verses, Genesis 1:26-27, and asked if anyone had heard of those verses being used by either the political right or left in justifying certain political rhetoric. Genesis 1:26, in which humankind is given “dominion over…all the earth and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth,” had been used to defend colonialism and environmental practices which over extract resources from the earth. Genesis 1:27, where humankind is made “in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them,” had been used by the political right to oppose gay marriage and transgender rights, but also by the political left to uphold transgender equality and nondiscrimination laws. “At every stage of the process of bringing the bible into the public domain, there are choices being made,” Chapman said.

In recent history, the Bible has been used far more by Republican politicians, which Chapman explained makes sense due to demographic shifts. White Evangelicals are a core subset of the Republican party, with 82% of Evangelicals planning on voting for Donald Trump in 2024. Democrats, however, find significant support with mainline Protestants, religious non-Christians, most Catholics and the religiously unaffiliated. Because Democrats are “racially and religiously more diverse,” explained Chapman, it makes sense that Republicans so heavily use the Bible whereas Democrats tend to shy away from religion altogether.

Chapman asked the attendees if they knew about the religiosity of four major Democratic politicians: Barack Obama, Kamala Harris, Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton. The audience was sure of Biden’s faith, but not the other three figures. Chapman revealed that all four politicians were not only religious by birth, but are all active members of their respective congregations and regularly practice their faith. This side of many Democrats is not known, according to Chapman, because of the pluralistic nature of the Democratic party. Because the Democratic base is so heterogeneous, prominent politicians choose to make religion less of an issue despite the religiosity of some of its members.

Chapman further explained why the Bible is used more heavily by conservative groups due to the differences in conceptions of religion between so-called “liberal” and “conservative” Christians, with liberal Christians being mostly composed of mainline protestants, some Catholics and some nonwhite Evangelicals. Conservative Christians, on the other hand, are almost entirely white Evangelicals and Mormons. While acknowledging that these were generalizations, Chapman described that conservative Christians believe in one universal Christian truth, while liberal Christians believe in the existence of some truths across faiths. She also determined that while conservative Christians value evangelism and feel obligated to share their religion with the world, liberal Christians are “uncomfortable or even embarrassed” with evangelism as a concept, and instead prioritize interfaith dialogue and mutual understanding. Finally, she spoke about the different views of the Bible between liberal and conservative Christians, with conservative Christians seeing the Bible as a, sometimes inerrant and infallible, guidebook for life, with liberal Christians viewing it as a “collection of interwoven stories of faith,” according to Chapman.

In 2016, 2020 and 2024, evangelicals have overwhelmingly given their support to Trump. When he was campaigning for the first time, though, “evangelicals were uncomfortable with Trump, they didn’t get on board with him immediately, they knew he wasn’t one of them,” Chapman explained. However, Trump “proposed a deal with them” according to Chapman, promising to give Christians more power in government and appoint pro-life Supreme Court Justices to bring Christian values back to government. Trump and evangelicals then began a sort of transactional relationship, and Chapman compared him to Cyrus of Persia, a biblical figure who, although being a non-Jewish foreign king, returned the Jews to the land of Israel after Babylonian exile and was the only non-Judean in the Bible to be called a Messiah.

Chapman zeroed in on a specific moment from the summer of 2020, a photo of Trump posed in front of a church holding a Bible. This event represented a “returning of the Bible to a place of power, a symbolic act rather than a ridiculous photo op,” Chapman said. The context of this photo is more telling, as the square in which the photoshoot took place had to be forcibly cleared out by police, as Black Lives Matter protests had been consistently occurring there. “He uses military force to re-introduce the bible into government power…it is seen as an object,” Chapman said. She explained that for Christians who saw the Bible as being under fire, this act was a counterattack.

“This move is a precursor for the January 6th insurrection,” Chapman said. She concluded that many Christian groups and leaders learned from Trump that violence is sometimes needed to sustain power.

In our current election cycle, voters’ view of Trump has changed. Whereas in 2016 he was seen in a transactional, Cyrus-esque role, Trump’s loss in 2020 and his assassination attempt this past summer have transformed him into a martyr, according to Chapman. His supporters believed that he was “saved” from death by God. Trump has bought into their new ideas by using increasingly apocalyptic language and transforming his rallies into religious services with religious invocations and hymns.

Chapman closed her talk by showing the difference between conservative and liberal lawn signs. While Republicans had signs with simple messages like “God and Country, Vote Trump,” Democrats had signs with many more words or complicated concepts like “Coexist.” “Democrats have beliefs that don’t fit neatly on a bumper sticker or lawn sign,” Chapman said.

This event was cosponsored by the Religion department, the Office of the Chaplain and the Elizabeth Nason Distinguished Women Visitor Fund.

Isaac Kofsky is a peer leader for the Office of the Chaplain.