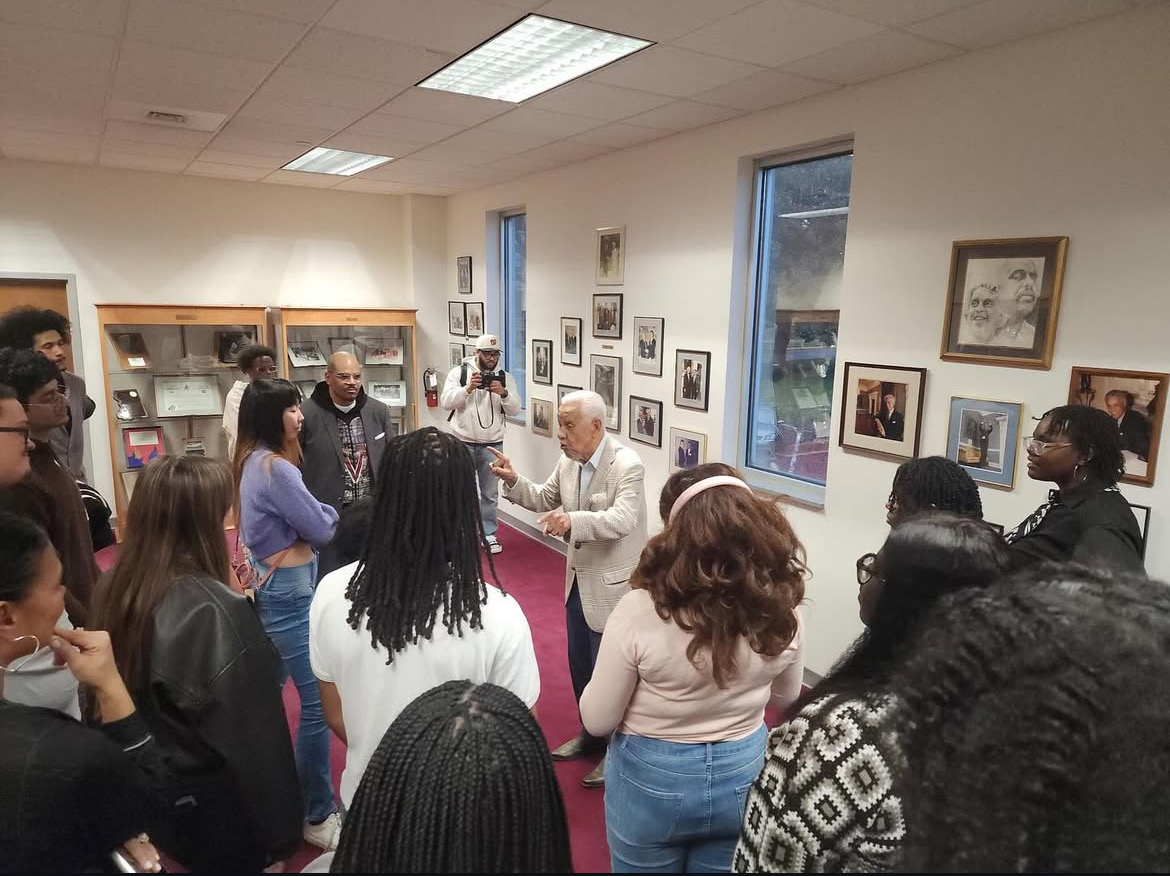

On Thursday, Jan. 18, Princeton University Professor Jack Tannous gave the Ira T. Wender Lecture in Middle East Studies. His talk was titled “From Syriac to Arabic: The Rise of Arabic as a Christian Language in the Middle East.” Tannous spoke to a classroom packed with students, faculty and staff about how Christians in the Middle East moved from speaking and writing in Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic, to Arabic, in both professional and religious contexts.

Medieval and Renaissance Studies (MARS) Director and history professor William North introduced the event by thanking the co-sponsors, the Ira T. Wender fund and the MARS department. He explained that the Ira T. Wender lecture series was made possible by donations, and is meant to “host a series of scholars in Middle East studies for short residencies to give lectures and engage with students.”

North gave context for the topic of Tannous’ lecture, saying that education of the history of the Middle East gives context to the current turbulence of the region. He explained that the Middle East has been incredibly diverse for most of its history, and sometimes people of different identities engaged with each other. At other times, they clashed with each other, but “their identities were more intertwined than we might think.” He then introduced Tannous as the lecturer, recounting his education journey from his undergraduate education at the University of Texas, his master’s degree at Oxford, and then his PhD at Princeton University, where he is now a professor. North and Religion professor Kambiz Ghanea Bassiri made Tannous’s visit a “centerpiece” of their course Religion 235: Religion and Identity in the Medieval Middle East.

Tannous prefaced his lecture by saying that he was going to focus on the transition from Syriac to Arabic. He spoke about two ways in which this change took place: the primary language of Middle Eastern Christians changed from Syriac to Arabic and the transformation of Syriac into Arabic, or the translation of sacred and academically important texts from Syriac into Arabic. He explained how this transformation began in the seventh century CE, when Arab forces colonized the Middle East, where the language of Christians at the time was Syriac. Over the next century, Arabic started to “seep into” Christian literature.

One of the primary ways that Middle Eastern Christians began to write and speak in Arabic was by becoming secretaries and scribes for the Muslim state very early in Arab colonization. At that time, by learning Arabic, Christians were able to gain a stable job, which meant that a substantial portion of the already small population of literate people learned to speak Arabic. Tannous said that Arabic “came through the side door” for Middle Eastern Christianity, being introduced by laity rather than “seeping down” from the clerical leaders in churches. These events meant that by the late eighth and early ninth centuries, there was a rise in people who spoke both Arabic and Syriac, and there was evidence of both written and oral exchanges between bilingual Christians who preferred to communicate in Arabic, even among themselves.

While Tannous spent a large portion of his lecture talking about the presence of Arabic in religious Christian communities, he emphasized that, for centuries, the majority of people who wrote in both languages and translated between the two were physicians and philosophers. He said that a group of translators in Baghdad translated a plethora of scientific texts into Arabic during the eighth and ninth centuries. Even though these were secular texts, most of the translators were Christians.

However, many Christian texts were translated into Arabic during that time, like the Old Testament written in Greek, otherwise known as the Septuagint, and a commentary on the Gospel of John. Tannous said that the latter demonstrated a shift from using Arabic as a language of “beating people up” to a way to engage in conscious conversation and criticism of religious matters.

Starting in the tenth century, manuscripts started to be published in Arabic, and were increasingly written for pastoral purposes. Tannous cited that this change was not welcome by all, reading an excerpt from a primary source demeaning Christians for “abandoning the beautiful language of Coptic [a language spoken in Egypt]” for Arabic in their churches. Additionally, churches and Christian leaders were translating Christian texts into Arabic for people who sought to know the doctrine of churches but did not know Syriac.

Ibn al-Tayyib, for example, made an abridged version of the canons, laws and important texts of Christianity into Arabic because he believed those who didn’t know Syriac, Coptic or Greek were “abandoning” sacred texts. Still, many Christians in the Middle East preferred to use Syriac for church matters and Arabic for professional ones. This trend continued until what Tannous called the “intermediate period,” where churches started to use Arabic more and more. This was followed by a series of historical events — violence against Christians in the Middle East, the invasion of the Mongols and the Black Death — which made Christians a minority in the Middle East. The Christians that remained, though, preferred to use Arabic in all matters.

Tannous used pictures of many primary sources throughout his lecture, including Syriac manuscripts overwritten with Arabic, religious and academic documents written in both languages, Syriac-Arabic dictionaries and many texts written in both Syriac and Karshuni, which is Arabic text written in the Syriac alphabet. Through these sources, he showed that biblical manuscripts were altered in their translations to Arabic to sound more like the Quran by using Muslim names for God and Christian prophets, to make the text more familiar for Muslim readers.

Towards the end of his lecture, Tannous emphasized that the transformation from Syriac to Arabic and from Syriac into Arabic was not uniform over all of the Middle East. The shift happened in different regions at different times, and sometimes even churches in the same ecclesiastical communities would have varied rates of change. Tannous continued, saying that in certain places, Arabic texts had to be “translated back into Syriac,” because the people of that region had not yet adopted Arabic.

Tannous described three basic phases of the Syriac to Arabic language shift. The first phase started when Arabic forces first colonized Syriac-speaking Christian Middle Eastern communities. The second phase was the gradual seepage of the Arabic language into the secular, professional and religious lives of Christians. The last phase, which Tannous claims “we are still living in,” is that of Middle Eastern Christians using Arabic as their primary language in all areas of life. In the present day, that is hard to track because of the diaspora of Middle Eastern Christians, but Tannous insists that Syrio-Arabic translations of crucial texts are still happening.