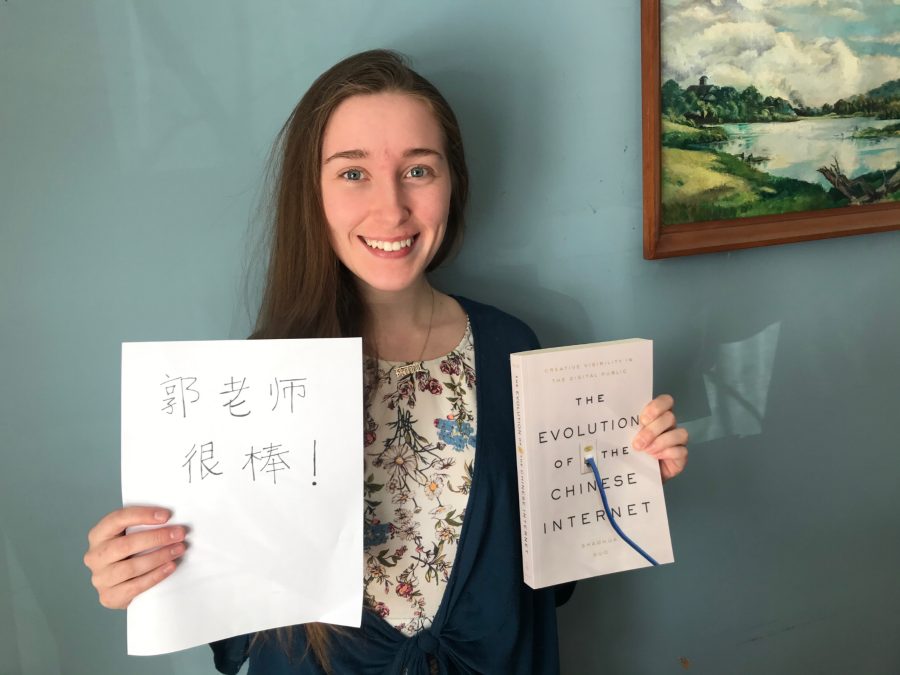

Professor of Chinese Shaohua Guo recently released a book titled “The Evolution of Chinese Internet: Creative Visibility in the Digital Public.” The release of Guo’s book was followed by a panel discussion on Wednesday, February 10, organized by Professor Asuka Sango, Director of Asian Studies. Panelists included Professors Kathleen Ryor, Noboru Tomonari and Carol Donelan, who commented on Guo’s research and recent piece of literature.

“The Evolution of Chinese Internet: Creative Visibility in the Digital Public” significantly expands upon and re-conceptualizes Guo’s dissertation titled “The Eyes of the Internet: Emerging Trends in Contemporary Chinese Culture.” In the wake of the opening of China’s internet in 1994 and the emergence of research about internet censorship in China, Guo was struck with curiosity.

Carleton Campus Directory.

“In contrast to the flourishing of research findings on what is made invisible online—such as the content that is being monitored, censored, and removed—we know little about the driving mechanisms that grant visibility to user-generated content,” Guo explained.

She often found herself asking questions like, “How and why an ingenious internet culture has flourished in authoritarian China? What roles do internet corporations, state sectors and commercial media play in China’s drastic transformation into digital society? And how do Chinese netizens navigate digital spaces to make sense of their everyday lives?” These questions inspired her to dive deeper into research and turn her findings into a book.

The research required and the writing itself were no easy tasks. According to Guo, “the project is based on a long-term study of the online space.” Between June 2007 and January 2019, Guo spent time in China engaging in field work and writing. She viewed the writing process as “a long journey,” that came to fruition in the form of a book. In addition to answering the questions that initially inspired her work, Guo noted her new publication “investigates digital cultural formation in China through the four most dynamic discursive spaces to emerge over the past two decades: the bulletin board system (BBS), the blog, the microblog (Weibo), and WeChat (weixin).”

Guo expressed how grateful she is for the company of her colleagues, mentors, friends and students: “[They] never failed to inspire me on all fronts and motivate me to complete the project.”

So when Sango suggested a panel discussion following the release of the book, Guo was extremely enthusiastic about it and took to inviting Ryor, Tomonari, and Donelan to participate.

Guo noted that she chose these three professors because they have been a part of the process since the very beginning, and have “offered me so much support and input throughout the entire process.” Furthermore, Guo recognized their research and expertise in the areas of media studies, art history and Japanese studies as “[aligning] with the interdisciplinary nature of my book.”

As panelists, Ryor, Tomonari and Donelan all gave brief presentations highlighting some of the main points of Guo’s book, and then posed some questions. According to Ryor, “this is the typical format for these types of events where faculty discuss another faculty member’s book.”

Ryor was glad to be a panelist at this event, noting that she has been on Guo’s review and promotion committee, and “[has] been reading her work ever since she was first hired.” As a professor of Art History and East Asian Studies, Ryor noted her connection to Guo’s work in that she is “interested in contemporary Chinese society….so the Chinese internet is naturally something that I naturally use and have interest in.” She followed by saying, “Guo’s book makes an extremely important contribution to studies of new media and creativity of the past 29 years in China.”

Donelan also commented on her interest in Guo’s work, specifically “Professor Guo’s proposal to shift internet studies from what is not seen on the internet (what gets censored) to what is seen.”

Donelan continued, “[Guo] defines the internet as a ‘network of visibility,’ a dynamic space wherein various agents compete for discursive legitimacy.”

Ryor’s presentation had two parts. She first highlighted four main points of Guo’s book. First, according to Ryor, it “analyzes the history of internet platforms in China and shows that there is a shift from an age of youthful innocence that celebrated idealism, egalitarianism and community effects to an era of commerce that openly commodifies original content and explores the business potential that new technologies bring.”

Secondly, Ryor said, the book “demonstrates the symbiotic relationship that has developed between entertainment culture and micropolitics,” and thirdly, it explores how “digital platforms have fostered creative visibility of user-generated content, cultivated technological innovation and mediated the formulation of social relations online.”

The last point of Guo’s book that Ryor touched on was that “her book also shows that while the modern public in China has agency that is nurtured by consumer culture, paradoxically the public is also susceptible to manipulation by those same commercial forces, as well as higher authorities such as the state.”

The second part of Ryor’s presentation then focused on the Chinese YouTube and WeiBo celebrity Li Ziqi to provide a foundation to raise some questions to Guo.

Professors Tomonari and Donelan subsequently gave presentations. Donelan articulated her presentation as “[focusing] on the mode of thought engaged by Professor Guo in her research, her effort to move beyond previous research that tends to think about the relation of the Chinese state and internet users in terms of static opposition rather than evolving hybridities.”

Guo was happy with the turnout of the panel discussion and appreciated the support from her colleagues, students and professors among other attendees. Guo said that if there was something she would hope those who attended the discussion and who read her book take away, it is the “importance of thinking outside the box, to critically reflect upon some of the commonly adopted concepts, languages and stereotypes in everyday life.”