“We buried him on the 50 yard line after midnight prior to the homecoming game, kept the dirt in a trash can and waited until half time. With the band playing, we ran out to unbury him, but we had been found out. The groundskeeper said he saw a slight variation in the 50-yard-line and thought it might be something, so he dug him out and gave Schiller to the football team,” said Paul Lampe ’79, about his experience with Schiller.

The Schiller bust is a part of a long-held tradition at Carleton. According to the Carleton sesquicentennial website, Friedrich von Schiller was a German poet, and his bust was part of a display in the Scoville Library. In 1957, student Bruce Herrick found the bust in storage and took it for room decoration. The next year, the bust briefly decorated the mantle of his off-campus house before it was stolen by another group of students. Thus began the decades-old tradition of stealing Schiller and going to great lengths to protect him. Eventually, another part was added to the tradition: that the keepers of Schiller had to exhibit him to the school at least once per year.

When Lampe was in school, he said “everybody knew who [Schiller] was,” and thought that pretty much everyone knew if you had the bust, you had to display it.

Kate Damberg ’81, who was also involved in the attempted football field Schiller showing, agreed. “If you had Schiller, you had to show him. That was the most important thing. Big events, Schiller should make an appearance.” However, Damberg commented that, “I’m not so sure it bore true for all four years I was at Carleton.”

Over the past couple years, Schiller has not been displayed as often.

COVID-19 has likely had an effect on Schiller’s presence on campus. Large events and gatherings where Schiller would normally make an appearance are no longer happening. Also, students have been required to spend less time in groups, which means the lore of the bust hasn’t reached as many people as it possibly has in past years.

The pandemic has been on the mind of Schiller’s current keeper, who said they have not displayed him. “Because of the COVID-19 situation, we decided public appearances with lots of people will not be happening any time soon.”

Alumni and current students show a strong understanding of the Schiller tradition. Joey Caradimitropoulo ’20 said that he obtained the bust his sophomore year. In his mind, “It’s no fun to hide it away. The fun is people trying to get it, and trying to keep them away from it.”

After having the bust for some time, Caradimitropoulo and his friends staged a showing of Schiller over reading days. They waited outside of the library at the end of the silent dance party, and when people started coming out, they held him up, and ran him across the Bald Spot to their getaway car.

Caradimitropoulo remembered the scene, saying, “People were tackling [the person holding the bust]. I remember throwing people off [him]. It was like a rugby game with Schiller.” Despite this, Caradimitropoulo and his friends managed to get to the car with the bust and make a safe getaway.

Honus Frohlich ’21 had a similarly chaotic encounter with Schiller. He was at Rotblatt when someone ran across the field holding the bust above their head. “A large crowd of people started following after him and trying to grab Schiller. There was a good amount of people tackling each other and ripping Schiller out of each other’s hands.”

Frohlich noted that movement is integral to the tradition. “Schiller likes to make brief passings in people’s homes and then continue on the journey. That’s the way it should be.”

An anonymous source echoed this, saying, the tradition “revolves around not just possessing, but presenting Schiller.” He then gave a possible reason for seeing less of Schiller. “It feels like it’s become more of a thing that happens outside the public discourse. It happens more on things like sports teams,” noting the exclusivity of it.

Caradimitropoulo agreed, saying, “More recently it has seemed to be exclusive.”

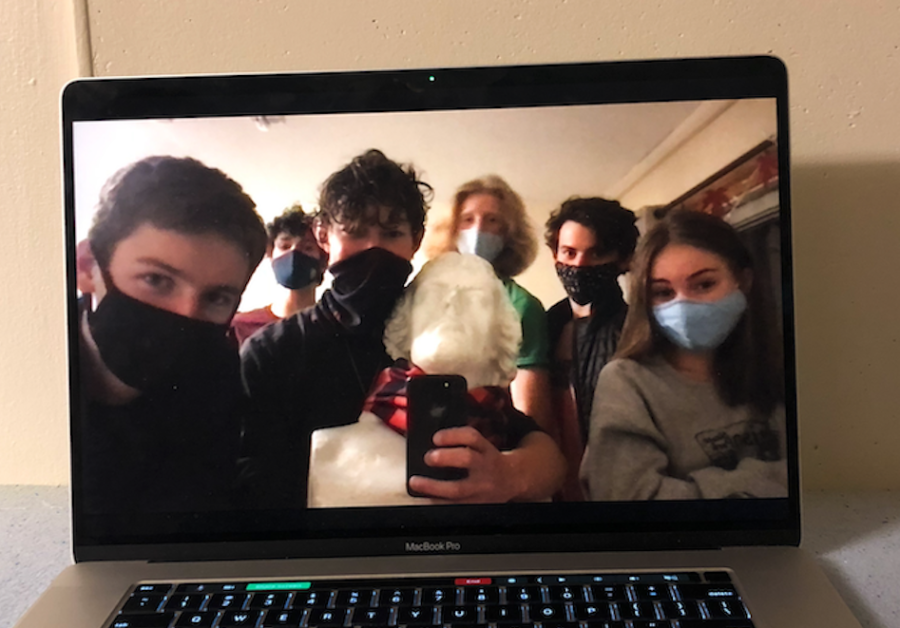

Photos submitted by students.

Sports teams are a likely bunch to hold Schiller. After all, athletes spend roughly 20 hours a week practicing together. In addition to this, they often eat meals and live together, forming close bonds. However, the Schiller tradition originated as something that united Carleton as a whole.

Evan David ’21, who is on the cross-country and track and field teams, noted, “It definitely circulates among sports teams. There’s definitely a mindset on the cross-country team that you want to have Schiller. And if you can’t have Schiller, it’s better for someone on the team to have Schiller.”

When Schiller was stolen from David and his friends, he said, “We were disappointed, but we were like, at least it’s still on the team.” He emphasized the competition between sports teams that plays out in the chase after the bust, saying, “It’s not like CUT took it from us.”

Alistair Pattison ’24, another member of the cross-country and track team, and recent possessor of Schiller, shared a similar sentiment. “I’d be much more annoyed if another team got it.”

“I think the main thing is that sports teams offer a way for traditions to be passed down. Younger athletes can ‘learn’ about Schiller from older athletes, while non-athletes might not have that opportunity,” said David. He concluded, “If I wasn’t on a sports team, I don’t know how I would have become involved with the tradition.”

However, the circulation of Schiller among sports teams is not to Schiller’s benefit. In David’s words: “The longer [the bust] stays with a certain group of people… I think that makes the tradition worse.”