On August 28, 2020, President Steven Poskanzer announced to the Board of Trustees his intention to step down as president following the end of this academic year while staying on as a professor of Political Science. Poskanzer’s departure ends an eleven-year tenure as Carleton’s president. Halfway through Poskanzer’s final term of leadership, Editor-in-Chief Emeritus Sam Kwait-Spitzer sat down with Poskanzer over Zoom for an exit interview — discussing, among other things, the president’s legacy, his hopes and anxieties for a post-pandemic future, issues of racial equity, climate change and his argument for the enduring (and increasing) value of liberal arts colleges. A less abridged version of this conversation will appear in the Carletonian’s online edition. This interview has been abridged for clarity.

Sam Kwait-Spitzer: You began your presidency barely two years removed from the greatest financial crisis in a generation. And you are leaving the college in the midst of a pandemic, amongst other crises. How have these bookends of crisis impacted your decade as president?

President Poskanzer: I don’t know whether you know this, but actually in the fall of 2010, when I started, there was a massive hundred-year flood in Northfield too. So it really kind of feels like I came in with a flood and I’m leaving with the pandemic. But actually, there’s an underlying point here that I really do think is very important. And that’s about the resilience of great colleges and universities. So, you know, there was a recession in 2010, but we came out of it really, really strong. We have the most applications we’ve ever had. The yield, the students who we admit who choose to come here, is at record levels. There’s more diversity in our student body. We’ve had a lot of success in hiring faculty and staff. We’ve had record-breaking fundraising. We’ve had new buildings. So we came out of that recession really strong. We’ll do the same thing from the pandemic, especially because I think this pandemic is very likely to reinforce the value of a residential liberal arts education.

SKS: Recently, you faced criticism from students for slow and immaterial responses to the murder of George Floyd and many other acts of racial violence. What are your feelings on both how you and the institution have responded, in the past months and years?

I would say that I think we are responding in very substantive and also very important ways to both the national and the local institutional imperative to address racism and racial violence. And let me give you some examples of the substance here. We’ve put in mandatory anti-racism training for all faculty and all staff and all trustees and all important volunteers. Carleton has never done that before. We launched a very focused and important community plan for inclusion, diversity and equity with a particular focus on the Black experience. And that’s something Carleton has never had before. That’s very substantive. We set up a George Floyd scholarship. We made donations to North Minneapolis community organizations. We’ve provided additional support to the Africana Studies program. We’ve created a whole new Office of Intercultural Life that is focused just on meeting the needs of BIPOC students. We’re hiring new BIPOC staff, especially in SHAC right now. We’ve promulgated a land acknowledgment statement to recognize on whose soil this college sits. With all of that said, I do think we really have to recognize that we live in a world where racism is still ever-present and at a college where racism is, of course, still present—and the work of making Carleton a truly inclusive college where everybody can realize their aspirations, I think that work’s not done yet. It’s far from complete, and we have to do that work right now.

When you started as the president of the college up until now, in what ways have conversations about race amongst the faculty and the institution changed?

Like I just said, you’ve got to start with acknowledging that there is structural racism that’s baked into the culture and the DNA of Carleton that is undeniable, and we have to work, and we have to work now in concrete and measurable ways to uproot that. You know, the fact that you could say the same thing, that there’s similar institutional racism at every other college or university, I don’t think that’s all that relevant. It doesn’t excuse us from the work that we have to do here that we’re called to do right now. And like I said, I don’t think that work really ever gets done, alas, but we’ve got to take the actions that we can take right now.

So from my perspective, I’m really proud of how much more diverse the student body is. Over my tenure, when I came here in 2010, we were about 27% historically underrepresented or international students. And now we’re 42% in 2021. That’s good, but that’s not good enough. I mean, we still need to keep going in that direction. I’m really proud of the numbers of BIPOC faculty that we’ve hired and especially the numbers of faculty of color that we’ve tenured over the last decade. I think our faculty is more diverse in gender and race as well. And, candidly, I’m also really proud of the senior-level administrative hires that I’ve made, who are committed to IDE work, and who’ve diversified that the senior ranks of administration here. But having said all that, I would like our student body to be even more diverse than it is right now, especially with more low-income and more middle-income BIPOC students. That would make us stronger still. And even though we’ve raised $125 million for need-based financial aid, I worry, quite frankly, that a Carleton education is still unaffordable for too many of the students that we would most like to have enrolled here. I hate it that when we’re making our admissions decisions, there are still times where we have to be what’s called “need-sensitive” in the trade. It’s like a wound in my heart. I wish we didn’t have to do that, but we know the answer to that. It’s getting more money and endowment, and more scholarships, and we can talk a little bit more about that.

One of the other things that I worry about—and maybe that’s the change that’s taken place in the dialogue over the years—is there are inequities in what I would call institutional capital. How ready folks are to take advantage of what college is like. I don’t know whether you’ve ever read any of Anthony Jack’s work about this. He’s a writer at Harvard grad school of education. And, you know, it’s one thing for a student who shows up at a college who comes from maybe an academic family and knows that going to office hours is a really good thing, and hears the word “syllabus” and knows exactly what that is. Some students don’t know that stuff when they show up at college. And so they are relatively disadvantaged in terms of just that institutional capital. And we’ve got to work to correct that even as we also work to correct financial imbalances, either for financial aid during the year, or—I’ve spent a lot of time and energy worrying about giving money and raising funds for summer internships so that somebody could afford to take an unpaid summer internship without having to sacrifice the money that they would otherwise have to work on to pay for college. Unless that playing field was even, BIPOC students, disadvantaged students are going to be at a further disadvantage. That’s not acceptable.

In your inaugural address in 2011, you asserted that “the sustainable stewardship of our planet is a defining issue of our time. Colleges and universities have an intellectual and moral obligation to engage deeply with this issue.” In your tenure, the college has taken many positive steps, like moving to geothermal heating and the expanded stewardship of the Arb, and continuing to be on track to hit the carbon neutral by 2050. However, the college’s public equity holdings continue to include companies that fund and engage in environmentally destructive practices, and the college has remained noticeably silent on the more recent Line 3 debate. What do you see is your environmental legacy?

Well first, and this goes through a bunch of questions. I’ve got to compliment you. You really read my inaugural address. I think that makes you, my mom, and me the three people who read it really carefully. So really, I appreciate it.

It was a joy to look back. Beautifully written.

Certainly one important thing here is that we collectively, as a community, developed and are really now hard into implementing a Climate Action Plan that includes both operational matters, but also really importantly includes an educational focus on climate change. And I will say here, the part of our legacy, the ideas that are being generated here at Carleton, by faculty and students in their scholarship—and especially the students that graduate from this place who care passionately about environmental issues and are equipped with the right type of intellectual tools to actually take action that will save our planet—that’s a huge part of what we need to do here. So I want to start with that.

But I would say probably that the centerpiece of my environmental legacy—and I’ll come back to that phrase—is the fact that Carleton’s carbon footprint has decreased by 53% from the baseline that we set in 2008. We did that because we’ve made major investments in campus utilities infrastructure, and we also made wise energy conservation practices. I would say to you that that’s a very rapid acceleration of that projected 2050 timeline for achieving carbon neutrality. We’re way ahead of where we thought we would be. And I’m proud of that. I think that’s critically important.

Now, I want to be modest here. This has happened on my watch, and I have certainly aggressively supported those investments and I’ve gone and fought for, you know, spending these monies to do that. But it’s really important to note that the progress here is the work of many, many faculty and staff. People like Martha Larson, who’s our manager of campus sustainability, student environmental associates. So, you know, it’s not like Steve made that happen. I don’t think it’s fair to take that kind of credit.

Let me go into a little bit more details and stuff that you asked about. Actually, I think you want to double-check with the investment office, because I think you’re wrong that we don’t currently have any public holdings in any fossil fuel companies right now.

There are no public holdings in fossil fuel companies, but there are a decent number of companies that kind of participate and fund various fossil fuel industries. These large companies are very connected, but I did want to press you on that a little bit.

We haven’t taken a public institutional stance on the Line 3 pipeline projects for the same reason that Carleton doesn’t take a public institutional stance on all kinds of other environmentally-sensitive development projects across the state of Minnesota. And we also don’t take a public stance on endorsing political candidates as an institution. We’re fundamentally an educational system, and so the places where we will take stances, as an institution, are going to be on educational things where we have expertise. Should there be affirmative action? Yeah. We know about that. That’s appropriate for Carleton to take an institutional stance on. Should there be educational opportunities available to DACA students? Yes. That’s an educational institution. Should a pipeline run in a particular place? Should this project get built versus that project get built? Those are not educational issues in the same kind of way. It’s entirely appropriate—it’s great—that individual students and faculty are engaged in activism and take on an institution, and taking a stance. Hopefully, we’ve equipped them with what they need: the knowledge to do that. But that’s different from whether Carleton as Carleton gets involved in those types of issues.

Broadening out, what are you most proud to have accomplished during your tenure? And what do you wish you had accomplished? And you did allude to this a bit earlier regarding endowed scholarships and not fully being able to be need-blind. Any other things that you’re very proud of and things you wish you had done?

There’s this old adage that, if you can, you’re supposed to leave the forest better than you found it. And so like that, I have always wanted to try and leave Carleton stronger than I found it when I came in. And I think that’s something that has been achieved by each of the presidents who came before me. I believe it’s true in my case, just in the same way that I believe it will be true for my successor as well.

So some of the things that I’m most proud of, I would say, are the following: I’m really proud that Carleton implemented a strategic plan that really set priorities for this place and made hard choices, including better career preparation for students, which was something that the college had really not paid as much attention to in the past. Increased socioeconomic diversity of the student body—and I’ll come back to that in a moment when we talk about scholarships and also collaborating with other liberal arts colleges—all that stuff came from our plan. But I’m really proud that we’ve raised already $430 million. We had a $400 million target in this campaign. We’re already way over it, and the largest share of that money is to endow scholarships for need-based financial aid. I’m really proud that Carleton emphasizes and has dramatically expanded need-based financial aid for low-income students and also for middle-income students. I would not want us to have a student body that is really wealthy, full-pay kids and really needy, full-need kids. You want the whole spectrum. Lastly, I would say I’m proud that our endowment value has increased. It was about $460 million when I walked in the door. It’s over a billion dollars right now. But in short, I would say the academic quality of Carleton is better over the last decade, and I’m really proud of that.

You know, I wish I had raised enough money that we could never take financial aid into account—but that will be hundreds of millions of dollars more before we get there. But every step we take towards that is great. I wish that we’d launched the IDE planning effort that we’re doing now five years ago, you know, 10 years ago. But you know, there’s an awful lot that I think we have gotten right. But there’s always more to do.

How do you think you have changed as a leader during your tenure?

I would say that I think when I came here, I was a pretty modest, unassuming person. I like to think that I am, but I can assure you that Carleton has made me even more humble and respectful of the wisdom of others. I am just constantly, regularly impressed by how smart, how devoted my colleagues, the administration, the faculty and the students are. And I learned from other people all the time. And in answering this question, I would also want to give a particular shout out to the staff of Carleton, and I don’t mean the vice presidents. I mean, the food service and ground crew, people and custodians that are the unsung heroes of Carleton. They have this incredibly deep knowledge of this place and how to get stuff done here. And in my experience, they try and put students first, and I learned a lot from watching them.

How did the nickname “Stevie P.” come about, and how do you feel about it?

Sure, so when your last name is hard to pronounce and hard to spell, a nickname is probably inevitable. But when I came here, one of the first questions people asked me was, “What do you want your nickname to be? What do people call you?” Students at SUNY New Paltz, where I used to be president, called me “Stevie P.” I actually like “Stevie P.” As far as nicknames go, it’s a pretty good nickname. It’s much better than the nicknames of other Carleton presidents that I’ve heard of. And maybe they had other nicknames that were even worse. Maybe I have other nicknames that are worse too. But I like “Stevie P.” And it’s also alright just to call me Steve too.

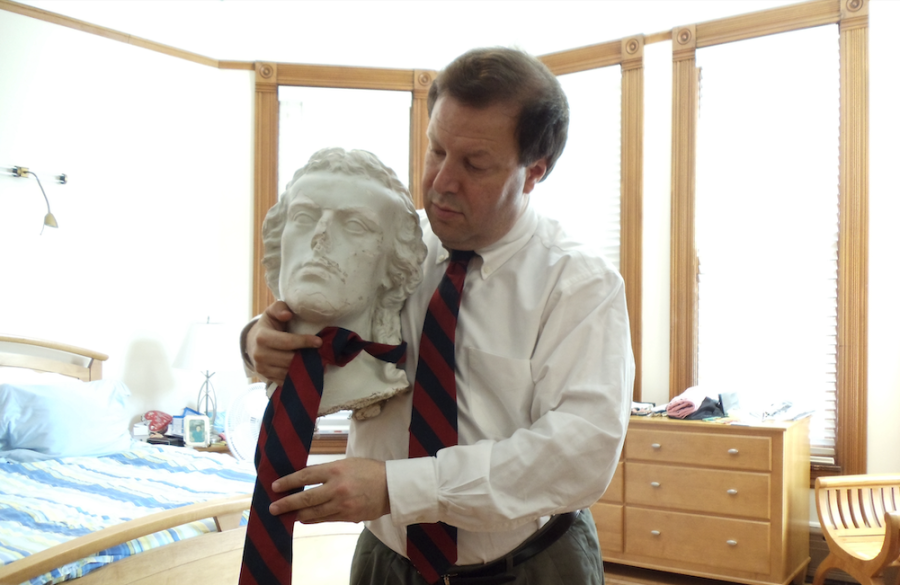

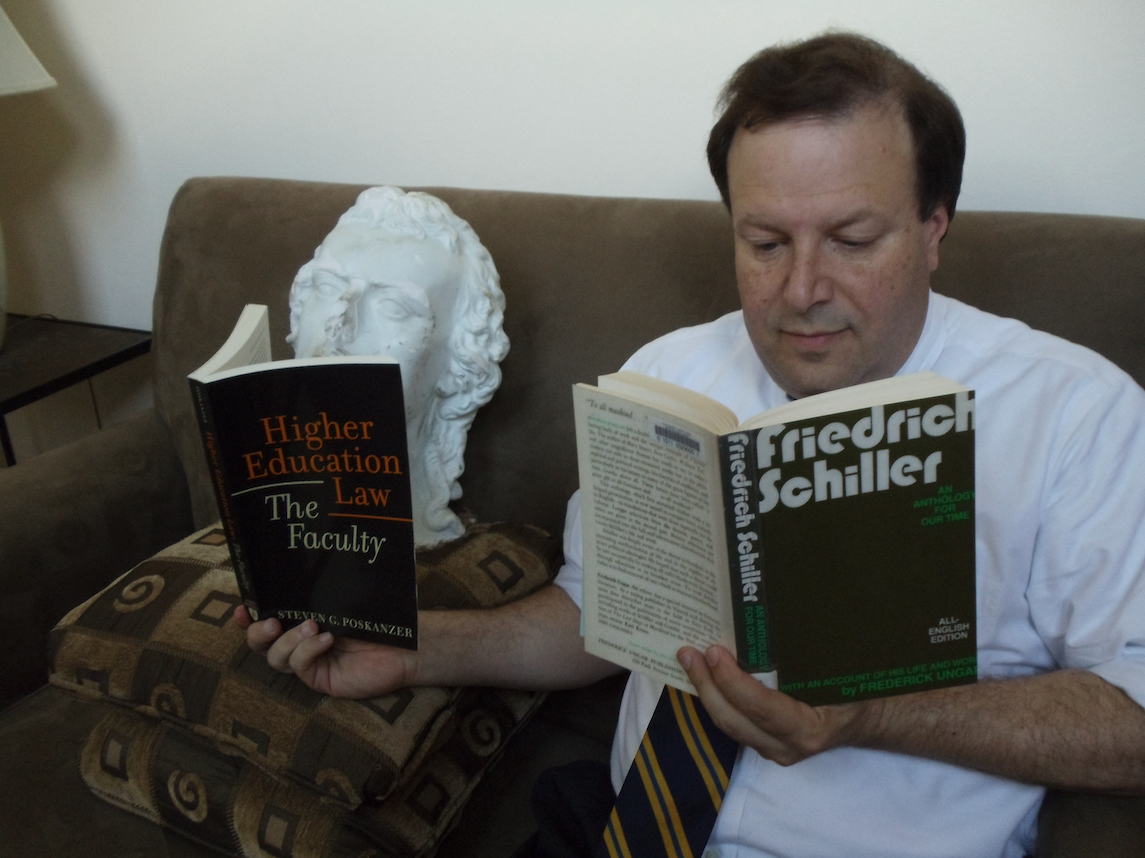

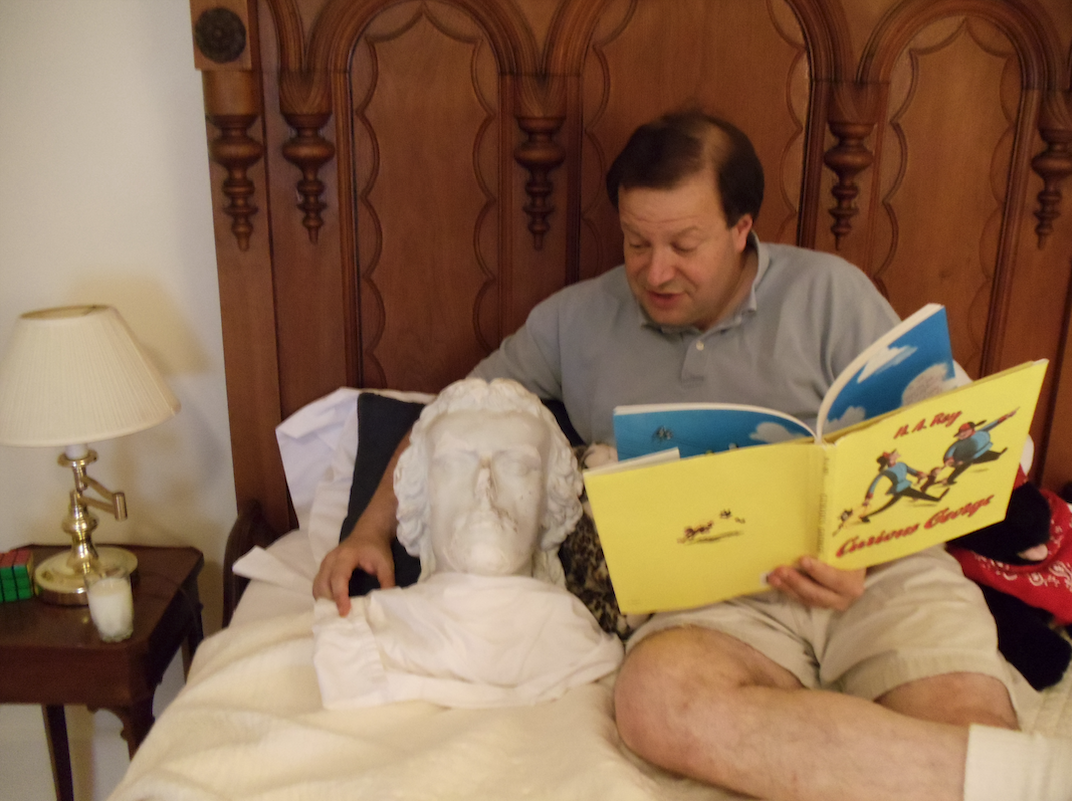

There is a photo pretty famous on campus of you shaving in the mirror while holding the bust of Schiller. And I’ve always been curious if it’s a real photo, or if it’s been expertly photoshopped. Can you comment on the authenticity of the photo and then if it is authentic, a little bit of the story behind it.

Okay. So there’s a long story behind it. So it’s absolutely authentic. I took it with a self-timer. In hindsight, I should have pulled the towel up a little bit more than I did. [laughter] So maybe not my best effort. It’s actually part of a series of photos from the fall of 2010, for the then-Guardians of Schiller. I had said when I was being recruited that I really wanted to be sure I met Schiller. And so the Guardians basically allowed me to borrow Schiller for a weekend if I would take a whole bunch of pictures of me with him. I am sad to say though, that because the Guardians have turned over, many of what I think are the best pictures of me and Schiller together have never yet hit the light of day.

I think there’s a picture of Schiller and me, me tucking him into bed with cookies and milk, and there’s a picture of Schiller reading my book and me reading Schiller’s book. And I think a picture of Schiller and me watching hockey together. If the Carletonian wants, I might be able to find some of those older photos.

Yeah. Well, when we publish this spread, if you have the time to find them we by all means would totally run them. If you have the time to find them!

You want them?

Yeah!

Alright! I will take a look. I think I might know where they might be.

Awesome!

But yeah, the towel photo is real. [laughter]

I assume you will no longer be living in Nutting House after you step down. What will you miss most about the house?

I don’t want it to be a mysterious place on campus. I love this house. The library in the house is my most favorite room. It’s really kind of cozy and classy and all the books are there. And I will really miss decorating the house for the holidays and having my family here. I will miss having pizza parties with students who we would troop up into the attic and into the basement and let see where the family that lives in the house really lives and play with the cats and dogs.

Now moving into the final section: “Looking forward.” Why have you chosen now as the time to step down?

So there’s kind of like a natural cycle to this job. What typically happens is a president comes in, they learn all about the place, then you do a strategic plan. Then you implement that plan. Then you run a capital fundraising campaign to pay for all the things you said you were going to do on the plan. And then you started all over again. And that cycle is now done this June with the capital plan and the strategic plan being implemented. And so I either needed to be willing to commit to another whole cycle of this, which would have been another seven to 10 years, or I needed to be willing to do what was right for the institution and kind of get out of the way and let the next person do it. And I felt if I started to do it again, that that would mean I will be president here for 17 or 18 years. That felt too long. It didn’t feel healthy for Carleton or for me.

In your inaugural remarks, you mentioned the growing potential for online education and also the indelible value of in-person education. So with the pandemic and the emergence of Zoom and other analogous programs, what is going to be the future of the liberal arts college in 10, 20, 50 years? And how has the pandemic changed this future? Speaking both about Carleton, but also the liberal arts college more broadly.

So I could write long essays about this. So I’ll try and give you a shorter answer instead. I’m absolutely convinced that a liberal arts education is still the best bet for smart young people. It’s the most flexible, capacious, adaptable type of education. And that’s what you need for a world that’s changing as fast as our world is. But I also think, and this is something I touched on earlier, I think the residential aspect of this is absolutely critical to the learning. And the pandemic has brought that back home to us, this hunger for human connection and seeing the value of being proximate to each other.I think that is more important than ever before. So I think the best liberal arts colleges, with strong reputation and good demand, are going to double down on residential character going forward, even as they’ll still take advantage of online things that are available. I’m a hundred percent certain that there’s going to be a continued robust desire for a set of great liberal arts colleges, and we need to be one of those. We’re one of them right now, but our responsibility is to make sure that we continue to be one of that handful of places.

This leads nicely into the next question. What will be the biggest challenge for the new president to solve at an institutional level and, relatedly and hopefully, in a post-pandemic era?

If you’re going to give generous scholarships—and we want to do that to bring in more lower and middle-income kids here, if you want to pay competitive salaries to faculty and staff, if you want to have the best types of facilities for teaching and learning, and if we want to support students in their emotional and their personal growth, which should be part of college, you got to have the wherewithal to pay for all of this.

And I don’t see us in an era where you can keep raising tuition in ways that are going to make the college less affordable, less within reach of families. And we can’t always assume that there are going to be generous donors who are going to step forward and do things. So that economic thing worries me.

Second thing that worries me, like I’ve said before, this is a moment where we have to center inclusion, diversity and equity work, because that’s how all faculty and staff and students at this place are going to succeed. And at the same moment that we have got to make that central to our work, we also have to reinforce and deepen what I would call the trust and the goodwill that we have at each other, and the grace, for lack of a better word, that we extend to one another. That’s a really hard thing to do right now when the pandemic has taken such a terrible medical and social toll, especially on people who’ve already been the most marginalized and disadvantaged in society.

Oftentimes, the political issues of the day feel like they are the largest political issues. And students on campus now will only be here for these four years. But can you speak to some other political moments and dynamics at the national level that filtered down to campus that maybe precede the students here now with a four-year window?

Sure, think about the fights about affirmative action, they’ve been going on for a long time. You know, this started in the 1970’s when I was in college, and there have been a string of Supreme Court cases that have chipped away at some of the rationales for affirmative action. I’m thrilled that Harvard won at the First Circuit Court of Appeals, but I’m very worried that that case is going to come down and end the ability to expressly take race into account to provide educational diversity.

I’m worried that there is a growing anti-intellectualism in society that questions science and questions truth, as provisional as truth sometimes is, and that picks on great colleges and universities, that thinks that they are just hotbeds of flawed thinking and wants to punish places like this.

It was very disturbing to me in 2017 when the government passed a tax that literally just taxes the endowments of private colleges and universities. They didn’t tax Texas and Texas A&M’s endowments, which are far bigger than Carleton’s endowment. There’s sort of an anti-educational spirit afloat in the world right now, and that’s troubling to me.

What does it mean to be an intellectual now with media being consumed in more bite-sized ways, like Instagram stories and Tik Tok and things like that? What is the unique value of learning in a more long-form way in an institutional setting?

It’s a great question. That value is absolutely necessary and as transcendent as it has ever been, and maybe even more important in a world where there is more flash, sometimes less substance, less time and attention and care given to issues.

We need to stop and really focus and pay attention to the things that need to be paid attention to. The really hard questions don’t have quick answers and don’t fall quickly into the purview of any one discipline. If we’re going to solve climate change, there is a biological element, a climatological element, a sociological, a political element, an economic element. You need all these things brought together. They need to be brought together in subtle and nuanced and complicated ways that understand the consequences. If we don’t have experts and we don’t listen to the experts, we won’t try and test the thinking of those experts in really rigorous, thoughtful ways that take time and attention and energy. We’re really not going to develop the good solutions. So I get that pace of the world moves faster. I get that people want quicker answers. Quick isn’t always best. Sometimes we’ve got to be more thoughtful and take the time to get it right, because the stakes are too high.

Moving forward to your successor, whoever they might be, what is on your list of must haves for the next president of the college? And what do you hope the next president brings to the office that perhaps you could not offer?

Yeah, I think this one’s for the search committee and the board to answer, probably not for me. If I started right now to list all of what I would self perceive as my deficits, we will never finish this interview. So let’s not go there.

What excites you most about Carleton’s future and what keeps you up most at night?

Let me go on to the more exciting stuff right now. I think the answer here is really pretty easy. It’s the students, it’s the remarkable young people that choose to come to this place and that embraced their studies and embrace this community. I think I really honestly believe that Carleton College students are the fundamentally most likable and thoughtful college students I’ve ever known. They’re smart. They’re curious, and they’re kind, and they’re caring and they’re funny.

I don’t know what you, this is an older story, but you know, previous presidents have liked to refer to Carleton students as being quirky. And when I came here, I had all these students come up to me and say, “Stop saying we’re quirky. We’re not quirky”

And I agree with the students because students are not quirky. Quirky has this kind of odd, weird, negative connotation to it. I think Carleton students are earnest. They’re idealistic. They want to make a difference in the world. They want the world to be better. They care about their families and their communities and their teachers.

These are amazing students, and this is why I work in higher education. Every single day I get to wake up and take care of and be part of a community that is full of this kind of young people. And that gives me optimism. That gives me faith, that the world will get better, that we can solve even daunting problems like climate change and racial injustice.

How would you like to be remembered as the college president?

I want to be remembered as an empathetic person and a forward-looking leader who was really devoutly committed to making Carleton stronger and better and who did so, but who did so while sharing credit with other colleagues, who did so always acting with integrity and always trying to put the long-term interest of the college first.

A year ago, the Carletonian had the opportunity to interview you in an article titled “Hopeful words in a wrenching moment: a Q&A with President Poskanzer.” We ended that interview with the question, “Do you have any last words of encouragement for the Carleton community?” And I’d like to ask you the same question to finish this interview.

There’s still some time to go, but based on where we are right now, what I would say is I have never been prouder of our students and seeing how considerately and how bravely they are navigating this year. That is an unprecedented, really awful and hard year. And then I really have the utmost faith in the future, of our students and in the future of this place.

Author’s note: After I turned off audio recording, President Poskanzer mentioned his intention to answer a final question we did not get to: his favorite Carleton meal. His answer: “A series of Bon App staff and professors will confirm: Chicken parmigiana and the Arcaine Burger.”