As temperatures drop in Minnesota, students will be spending more time indoors, which is exactly where COVID-19 has the potential to spread – via contaminated aerosols.

“An aerosol is, by definition, any solid or liquid suspended in a gas; in this case, the gas is air,” said Dr. Deborah Gross, an aerosol scientist and professor of chemistry at Carleton. She added that there is no perfect size at which something goes from being called an “aerosol particle” to being called a “droplet,” but aerosol particles are smaller and linger longer in the air. These particles can be produced by many different forms of exhalation – including breathing, talking, yelling, singing, sneezing and coughing.

Initially, no one was certain whether COVID-19 could be transmitted via aerosols, and the World Health Organization dismissed claims that it was an airborne disease. In July, a number of scientists appealed to the medical community and to relevant national and international bodies to recognize the potential for airborne spread of COVID-19.

Prof. Gross said that “the delay in acknowledging airborne transmission [by the WHO and the CDC] definitely had an adverse impact on development of mitigation strategies and gave people a false sense of security about ‘social distancing,’ as it implied that it was safe to be 6 feet away from someone whether or not they were infected with COVID-19.”

The smaller or more enclosed a space is, the more likely airborne transmission will occur. Prof. Gross explained that the aerosol particles that contain the virus can linger in the air for hours or longer. They may also settle and remain on surfaces for hours to days, depending on the composition of the surface.

As campus enters the third week of Winter Term, airborne transmission of COVID-19 is an even greater concern. Steve Spehn, director of Facilities and Capital Planning, is a member of the Facilities and Ventilation subcommittee, one of many committees formed by the college in response to COVID-19. He said they began by looking at recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) and the Minnesota Department of Health.

Based on ASHRAE guidelines, Facilities then worked to install MERV 13 filters wherever possible. For filters used in HVAC systems, “MERV 13 is the minimum filter efficiency that is recommended for filtration of particles that are of the size we care about as possibly containing SARS-CoV-2 virus,” Prof. Gross said. Previously, most campus buildings contained lower-grade MERV 8 filters, which were enough to catch pollen and dirt, but not the smaller particles produced by COVID-19.

According to Maintenance Manager Mitch Miller, the installation process itself is simple—it’s just a matter of taking out the MERV 8 and replacing it with the MERV 13. It gets more complex, he said, because the higher the filtration level, the more air restriction it causes. To offset this reduction in airflow, the fan speed must be increased.

However, in some of the older buildings—like Willis and Leighton—increasing the fan speed was not an option, so the MERV 8 filters were kept in. Miller said, “We didn’t have the ability to offset the pressure against the filter, and [the MERV 13] just restricted it. And then you end up losing airflow in the space, which is counterproductive in trying to increase the safety level.”

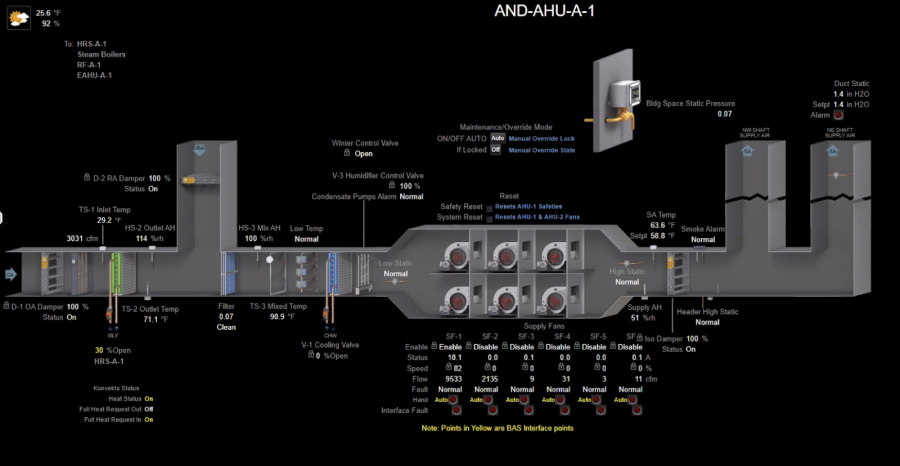

The newer buildings—the Weitz Center for Creativity, Anderson Hall, and the Language and Dining Center (LDC)—were all able to accommodate the higher-efficiency MERV 13 filters. These filters have to be changed out twice as frequently, but their status can be monitored online using building automation software (BAS).

Facilities also used a formula to calculate the air changes per hour (ACH) in each space on campus—based on the filtration rate, percentage of fresh air and percentage of returned air—which was then used to determine room occupancy. Miller added, “We tried to get at least four changes per hour in every space. Some exceed that, some were a struggle to get there and some just plain we couldn’t make it.” In the SHAC respiratory clinic, the air change rate has to be even higher—closer to 10 to 12 air changes per hour.

In some of the spaces where they could not achieve the minimum four changes per hour, Facilities placed standalone, portable HEPA filtration units. According to Prof. Gross, “HEPA filters are the gold standard for filtration—they are certified to remove 99.97% of particles that are 0.3 micrometers in diameter.” Over winter break, Facilities also installed the first bipolar ionization unit in Leighton Hall, which releases charged atoms that attach to and deactivate virus particles.

Miller explained, “It’s a newer technology, but it’s basically a scrubbing of the air as it passes through the air handler, eliminating all bacteria and virus. It enhances filtration considerably and allows us to get the capacities where we can actually hold class in there.”

While these new ventilation systems are critical, they are not sufficient. (The “Swiss Cheese Model” of pandemic defense helps explain the need for multiple mitigation methods.) Students also need to follow the occupancy guidelines set for these rooms, Spehn said, “because it’s not just based on physical distancing, it is also based on ventilation.” These capacities are listed on the doors of all spaces and reflect the total capacity of the space, including students, instructors, lab assistants and other approved visitors.

Whenever you are in a room with someone, you are breathing the same air, which comes with a risk for transmission. Prof. Gross recommends making sure everyone keeps their mask on when you have to share spaces with people outside your pod and trying to minimize any activity in which you have to remove your mask inside a shared space, such as eating. Prof. Gretchen Hofmeister, who also serves on the Facilities and Ventilation subcommittee, agreed.

“The capacity changes haven’t changed the protocols that are in place for indoor spaces: everyone should wear masks that cover their nose and mouth, sanitize their hands upon entering and exiting spaces, sit or stand six feet or more away from others and eat only in designated areas,” she said.

Natalee Johnson, coordinator of medical services at SHAC, also emphasized the importance of student compliance with testing. This winter, Carleton has doubled their asymptomatic surveillance testing regimen to test 600 individuals per week. “We’re really bumping that number up to make sure that we’re catching things early,” Johnson said.