The 1918 flu killed 675,000 people in the United States, with over a quarter of Americans sickened. Worldwide, the death toll was between 50 and 100 million This was no ordinary strain of the flu. According to John M. Barry in “The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History,” the 1918 flu was an unusually fatal, hybrid virus that originated at Camp Funston, an army camp in Kansas City. It spread quickly in the trenches, barracks, and hospital tents of World War I soldiers—where students in Carleton’s Student Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C.) could soon be deployed.

On October 1, 1918, the Carletonia—so the Carleton newspaper was called at the time—hailed the establishment of Carleton’s S.A.T.C. as “one of the greatest and most significant events in the history of Carleton.” In addition to a modified academic course-load, students inducted into the S.A.T.C. would live in military barracks and train in preparation for deployment to the war front.

To mark the occasion, Fred Hill, a Professor of Biblical Literature and a revered moral authority at Carleton, gave a speech in the Chapel, in which he praised the college’s support of the war effort and spoke hopefully of the soldiers’ futures. According to the Carletonia, Hill believed the war would turn them into “worldly citizens” with an “expanded world vision.”

At 5:00 PM that afternoon, First Lieutenant F. E. Lord of Louisville, Kentucky ordered the newly enlisted members of Carleton’s S.A.T.C.—just about all of the men enrolled at the college—to quarantine themselves in Sayles-Hill Gymnasium.

Quarantine on Campus

Although the “Spanish Flu” was already sweeping the country, killing 195,000 people in the U.S. within the month of October alone, the Carletonia projected a patriotic and self-assured attitude towards quarantine and the evolving epidemic.

“Quarantine,” the Carletonia explained, “is a war measure… [that] is to be looked upon as a privilege and not as a hardship.”

In fact, much of the country underestimated the severity of the Spanish Flu epidemic. Historian Nancy Bristow suggests that this calm was a result of the government and popular press’ suppression of critical information. President Woodrow Wilson never spoke publicly about the pandemic, and war censorship led reporters to downplay the disease in order to boost morale.

Since Spain did not participate in World War I, Spanish reporters could openly share information about the disease with the public. This lent the appearance that it was also the only place where people were really sick—hence the misnomer: the “Spanish Flu.”

In Northfield, campus authorities hoped to keep students sealed off from the outside world until the virus blew over. “The quarantine rules laid down by the authorities of the college are for the purpose of protecting the students against the outside sources of disease,” reads an October 22 Carletonia column.

Though students were strictly separated from outsiders, the rules on campus were more lenient and left many decisions up to the individual. The Carletonia notes “the uncertainty of quarantine rulings at Carleton both as to duration and restriction.”

The on-campus rules that did exist tended to come from military personnel.“The people who were in charge of the S.A.T.C. had a really big role in deciding what the rules of quarantine were,” said Carleton Archivist Eric Hilleman.

The precautions seemed to be working; by the end of October, the virus had not yet reached Northfield. In an October 29 Carletonia, a student noted that the “students of Carleton have thus far been most fortunate in escaping the influenza epidemic.”

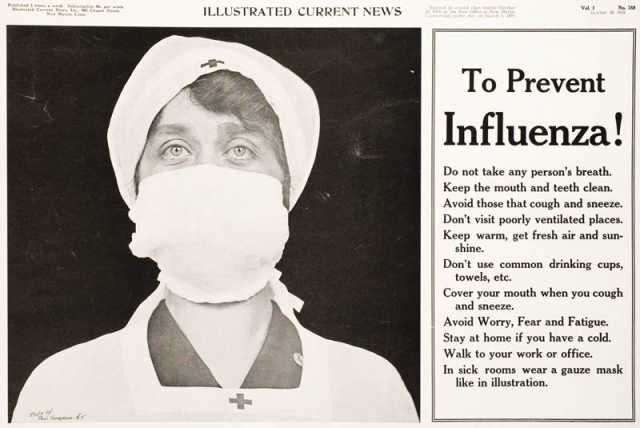

Yet they remained on high alert: “The most extreme precautions must be taken in regard to damp clothing, sneezing, and general care of health if we would continue in our present fortunate condition.”

Uncertainty, Yet Optimism

On October 22, the Carletonia reported, “Altho is it not known exactly what day the quarantine will be lifted, it has been rumored that the men may be out some time this week if, as at present, there are no cases of influenza in the locality.”

However, in response to reports of several influenza cases on campus, the quarantine persisted and even became stricter. A November 12 Carletonia article reads, “No one is permitted to leave the campus except in case of extreme necessity,” a protocol that was enforced, according to the 1919-20 Algol yearbook, by “stern sentries.”

After three games for the co-collegiate S.A.T.C. football team—the sole season in which the Carleton and St. Olaf teams combined—the rest of the season was called off due to the quarantine. The college also cancelled an intramural match against the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, a concert series, and a visit from the British Educational Mission, an envoy of British professors sent to the U.S.

On Halloween, the campus was purportedly quiet.

Even the Carletonia—at this time, not entirely a “student paper,” as it was overseen by a Board of Publishers—considered temporarily suspending publication. The Manitou Messenger, St. Olaf’s weekly paper, was indefinitely suspended due to quarantine, but the Carletonia decided to continue publishing.

“The Carletonia is being published with considerable difficulty thru the period of quarantine. Not only is there scarcity of news, but campus rules prevent the editors from working with the freedom essential to their convenience,” wrote a student. “It is believed that the men, being entirely cut off from the rest of the college, have practically no other effective way of becoming informed of college news than thru the weekly publication.”

As students weathered the quarantine into its fourth week, there is evidence that they no longer merely felt stoic about their situation. Quarantine had transformed the campus, disrupting students’ social lives and forcing class cancellations. And, by November 14th, 40 S.A.T.C. men had come down with the flu.

Two Quarantines

Men and women at Carleton enjoyed different degrees of freedom throughout the 1918 quarantine, even (and perhaps especially) in November, when the college instituted its strictest quarantine protocols.

From the outset, campus authorities prioritized isolating men. While the men enrolled in the S.A.T.C. had officially been confined to the campus for weeks, the November 1 issue of the Carleton College News Bulletin (a rough analog of The Voice, Carleton’s alumni magazine) reported that the women had “voluntarily placed themselves under restrictions almost as close as those of the men.”

While women might have chosen to abstain from hosting guests from out-of-town or from venturing off-campus “except on errands of necessity,” the college required male students to remain in isolation. The college would officially issue a similar quarantine for women, but only after several students had become sick.

Carleton History Professor Amna Khalid, whose scholarship focuses on the social dimensions of disease, suggested that men might have been treated differently during the quarantine because of their role as soldiers during World War I.

“I wonder to what extent quarantining men was a way of reserving people that might be necessary for the war effort,” Khalid posed. “Or because of the way in which the incidence was higher in men, their lives were perhaps valued a little differently.”

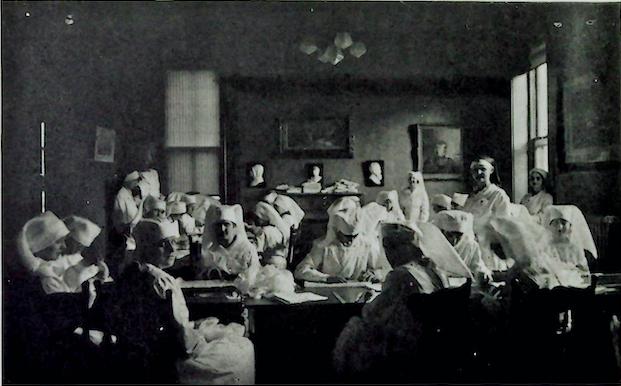

By mid-November, while none of the women had contracted the flu, more than 40 men in the S.A.T.C. were sick. To stop the spread of the virus, the college instituted its most extensive quarantine measures yet—separating the campus from the town, the men from the women, and the sick soldiers from the healthy.

According to the Carletonia, contact between men and women on campus deteriorated as a result of the stricter measures.

“A three-fold system of quarantine such as we are living under, cannot but prove disastrous to the normal social relationships of a college. The binding rules of segregation, while most valuable and effective in preserving our health, have necessarily made social intercourse impossible. Therefore, any visible co-operation [between men and women] has been out of the question,” a student wrote.

With the men in quarantine or in military training, Carleton women took on new roles and responsibilities on campus—including on the Carletonia editorial board. The year 1918 was not only the first year that a woman held the position of editor for the Carletonia, but at the beginning of the year all of the newspaper’s editors were women. Carleton women also sustained the college’s financial support for the War Work Campaign—a national fund devoted to promoting the morale of soldiers stationed overseas.

When there were no more men available to work as waiters at Carleton’s Gridley dining hall, women signed up for the job. “The women have become to all appearances as efficient as the men,” remarked the Carletonia, “and their greatest satisfaction is that they are receiving men’s wages.”

Because all co-ed programs were cancelled due to the quarantine, Carleton women also sustained the college’s social life and student activities. They organized and facilitated several on-campus events, such as the annual Thanksgiving celebration on November 26.

Under the auspices of the Red Cross, Carleton women also collected fruit for the sick and made hundreds of masks for student use on campus.

Professor Khalid notes that while World War I is often credited for “expediting” the women’s rights and labor movements, “a great part of it was actually the flu: the fact that it was debilitating men more than women was one of the reasons that women did come out and take on more public roles,” she explained.

“It’s kind of that silver lining, of sorts, that comes with all pandemics—which is not to say that we should celebrate pandemics or that they’re a good thing, but I do think that in terms of looking at the impact, it’s complex.”

As the quarantine dragged on through the end of November, women and men remained on opposite sides of campus, with the Carletonia as one of “the last means of connection” between them.

Christmas Vacation

On November 26, nearly two months after Carleton had begun its quarantine, the Carletonia announced that the men in the Carleton unit of the S.A.T.C. were to be released—“in all probability the quarantine will be lifted some time this week and academic work again resumed.”

The Carletonia reveals that the college began to make plans for the return to classes. Particular courses, like Plane Trigonometry, were slated for extension and students were instructed that “those who wish to change their courses should consult with their deans immediately.”

Two weeks after the Carletonia ran the headline “Influenza Situation is Greatly Improved,” a nearly identical December 3 headline read, “Influenza Situation is Rapidly Improving.” No new cases had appeared, and the 36 students still hospitalized were reported as “convalescing.” The quarantine officially ended three days later; no members of the college had died.

Meanwhile, St. Olaf had not been as fortunate. The November Carleton News Bulletin noted, “In spite of the most energetic and heroic work on the part of [St. Olaf] college and physicians, the lives of four students were lost.” The Manitou Messenger reported that the number of influenza cases on campus neared one hundred.

On December 6, the same day that the Carleton quarantine was lifted, St. Olaf abruptly ended the semester and sent students home to begin Christmas vacation early.

With the quarantine lifted, Carleton students also prepared to leave for Christmas vacation, feeling fortunate that no members of the college had been lost during the quarantine.

The Carletonia staff—who had continued to report throughout the duration of the war and the quarantine—wrote a parting message to students as they left for Christmas break: “In this long period of contact with each other,” wrote the editors, “we have revealed both our good and our bad qualities with unusual vividness. And, as is too often true, our bad qualities have become more prominent than our good.”

“Our nerves are tense and our minds at the breaking point,” they added.

If the stresses of prolonged isolation and the threat of sickness had somewhat fractured the Carleton community, the editors hoped that students could reflect on the experience over break.

“Let us take this long-needed vacation for its full worth. Let us find the undesirable traits in ourselves and banish them that we may return unhandicapped with the new year,” they suggested, “and while we are going thru this period of reconstruction, let us not forget that we owe ourselves a complete rest from our long period of unbroken labor.”

After students returned from Christmas break, the Carleton community coped with one loss. On January 29, beloved Professor Fred Hill died from complications of the flu. Hill had become ill in mid-January and struggled to recuperate after contracting pneumonia. “People came back from their breaks and life was returning to somewhat normal, but then Carleton did get that one huge blow,” described Hilleman.

Today, historians are reopening accounts of the 1918 pandemic, in an effort to understand COVID-19.

Julia Miller • Apr 24, 2020 at 3:39 pm

This is a really fascinating deep dive. I am really impressed with all the different angles you covered and this was an incredibly interesting read especially now to notice the similarities and differences 100 years later with the world and with Carleton.

Dan Ashurst • Apr 3, 2020 at 6:50 pm

Very interesting and hopeful retrospective. I was curious about how the college responded to pandemic in 1918 just the other day.