Not too long ago, I wrote what ended up being a con- troversial article titled “Yes, STEM is harder”. Within it, I concluded that if we use GPA as a metric, STEM and humanities classes are on an even playing field difficulty-wise. However, in my observation, student opinion did not seem to yield the same results. Should my attempt at qualitative research be sound, then why should there be a discrepancy in difficulty, but not grades?

The obvious answer is that GPAs are a flawed way of looking at the amount of work, effort or learning a student was able to undertake. This is true for a number of reasons. The one most people love to quote nowadays is grade inflation. Because more people are going to college, more people are competing for the same number of jobs and graduate school positions. As such, a higher worth is attributed to your GPA. Then professors feel guilty about locking you out of said opportunities, leading in turn to higher grades. Colleges also need their students to achieve favorable GPAs if they are to boast graduate school and job placement rates to incoming students. This argument, of course, leaves out the fact that college admissions too has become more competitive. The work that could once get you into the most elite colleges is not half of the work that is required now. Could it possibly be that we are now breeding a stronger work ethic in high school and so students are more likely to perform better in college, leading to a natural increase in grades?

Another case against GPA is the phenomenon of grade shopping. This is something that most, if not all, college students who put worth into their GPA are guilty of doing. Not all classes are created equal. In fact, not all instances of the same class are created equal. In the article I previously mentioned, I used my computer science class as an example of extreme difficulty in STEM. I can almost guarantee that should I have taken it a term later, with a different professor at a different time I would have gotten a better grade and I likely would not have written that article. I know this because it’s a rather open secret among students. When I discuss the difficulty of a class with my peers who have already taken it, it’s rather obvious when a professor is making it harder than it needs to be. These discussions then lead to a self-selection of classes that will let a student “shop” for a better GPA.

The third issue is the lack of context for your grades. I would not be surprised to find out that grades during online classes and in-person classes varied greatly. If the classes were taught at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, how is that affecting the psyche of students? Are online examinations an effective way to judge student knowledge versus in-person ones? None of this is included when it comes to a three-digit average.

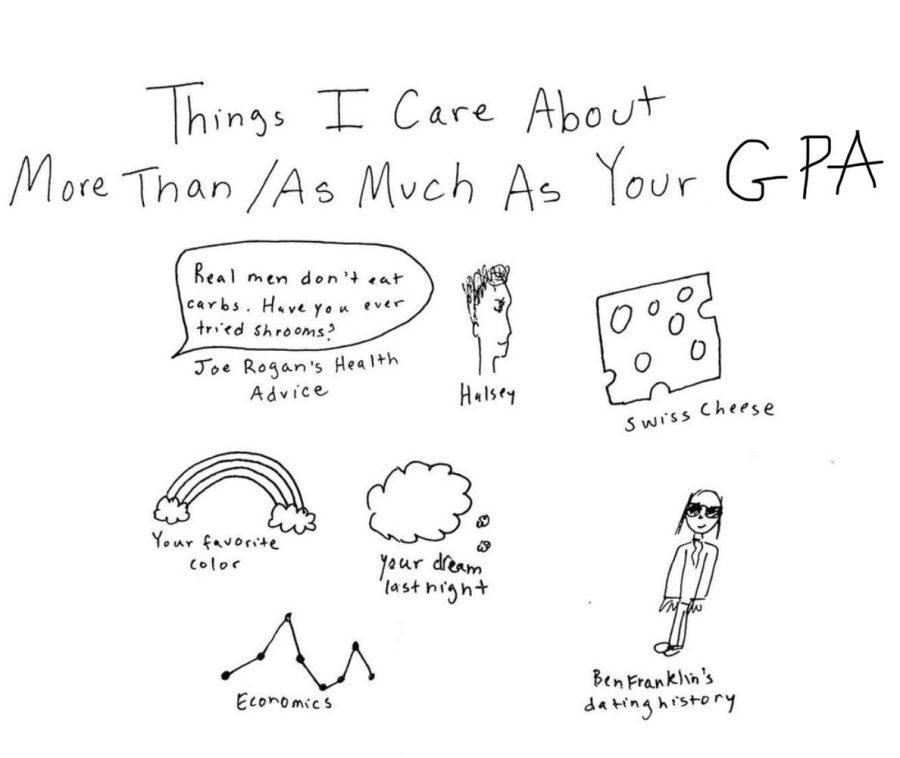

This is not a novel argument. Already commonplace are arguments against basing your self-worth around your grades, insisting that high GPAs are not necessary to succeed in life. Although this is a true statement, it does not erase the anxieties that students nowadays face when it comes to worries of GPA. Self-worth, job opportunities or graduate schools are all examples of the reasons why a student might place their GPA above other things, namely, learning. Even though we now try to place less emphasis on a student’s grades, these previous reasons are still very relevant to us today. As such, it is a useless undertaking to continue the same messaging attempting to dissuade students from worrying about their grades. A better approach lies in bettering the system we use to qualify students’ performance.

Enter the GPAM. An initiative by Bucknell University, the Grade Point Average Median seeks to remedy the issues of grade inflation, grade shopping and context. The GPAM is simply a second number which indicates the GPA you would have should you have achieved the median grade in all of your courses. Your GPAM would be displayed on your transcript besides your GPA, allowing one to appreciate the comparison between the two. For example, say you have student one and student two. Student one is a student with only two easy courses on her transcript where she got two A minuses. Her GPA as a result is 3.67. Most of those in her two classes performed similarly to her, so her GPAM would also be 3.67. Student two took a very difficult schedule however, but was able to study hard and secure a B plus and an A minus. The rest of the class did not do as well, and the median was a B. Their GPA+GPAM would be 3.5/3. From a GPA perspective, student one takes the cake. From a GPA+GPAM perspective, student two has the upper hand.

With this, grade inflation would be addressed on a course-by-course basis. If everyone seemed to achieve an A in a class, the difference between your GPA and GPAM would be unchanged, but your GPA would still rise. If you simply selected the wrong section for a class and everyone seemed to perform poorly, your GPA+GPAM calculation would reflect that accurately. Similarly, the person who took the class online would be judged by a separate set of standards as the person who took it in-person a term later, based on how well the class performed in general. This would also allow professors to award the grade they feel is actually deserved versus which grade they should due to societal factors.

This system does bring the issue of comparison. You ideally want your GPA to be much higher than your GPAM to show that you put in the effort to perform better. Your GPAM however, reflects your classmates’ grades. Of course the last thing professors would want to do is to create a competitive environment in classes. As such, I would argue that most classes where the distinction between GPA and GPAM would be most pronounced are graded on curves already, and the collaborative spirit of Carleton students is still present. Additionally the GPA+GPAM metric is not one that should completely take the GPA’s place, but one that should be used for specific instances where comparison is already inherent and context is necessary like graduate school admission as well as distinctions in commencement.

With this metric in mind, students would be a lot less worried about how well they can “game” the system for their benefit. Instead, they’d be a lot more worried about taking the classes where they feel they can learn the most, fulfilling Carleton’s purpose as a liberal arts college.